Paris

July 7th-16th

City in Context

Over the past hundred years, Paris and the greater Ile-de-France region have undergone profound changes in transportation. In 1900, the city opened it’s first metro line for the World Fair, and by 1909, 63 kilometers of track had been laid. Entrances to metro stations were designed by Hector Guimard and the quintessential Art Nouveau style. At this time, central Paris had reached it’s tipping point with overcrowding. The medieval Thiers Wall was dismantled, but a great debate stirred in how to connect Paris with the “banlieues” or suburbs. In 1925, modernist architect Le Corbusier presented a provocative idea for the refurbishment of Paris called the Neighbour Plan, in which all the central arrondissements would be destroyed and replaced by a modern city made up of Towers and express tollways.

Many didn’t agree with Le Corbusier’s vision of Paris, particularly with the notion of abandoning Paris’ architecture for high-rise, single-use towers. But Parisians, like many urbanites in the rest of the western world, saw the need for an automobile-oriented city. The private car became affordable and ubiquitous in the 1960s, and the city subsequently had to be adapted to allow for smooth and quick travel by car. In 1960, roadworks began for the Paris ringroad, which still delineate the city’s boundaries with the Banlieues today. A network of expressways were recommended to relieve traffic within Paris, including along the Seine River.

At the same time as the road network was expanding in Paris, so too did public transport. Regional guidelines of 1960 and 1965 stipulated the development of RER rail lines which connected banlieues to central Paris, giving rise to the creation of major connecting stations at Etoile, Auber, Chatelet, Bastille and Nation. In the 1970s-80s, the oil crisis and environmental awareness led to the promotion of more space efficient transport and public spaces. This was also accompanied by new regional guidelines (Sdrif) which brought two new networks, Meteor and Eole, within Paris to link up mainline trains stations and provide transport in new, developing neighborhoods. Since 2001, a tram network and dedicated bus lanes have been implemented. In 2013, the Grand Paris Express project was announced, the largest public infrastructure project in Europe. Over the years, the size of public transport networks have increased in line with the growing population of the Ile de France region.

In terms of active transport modes, the city has recently made improvements to the built environment with pedestrianization projects and the expansion of bike lanes. In terms of cycling, an ambitious “Plan Velo” seeks to double the total length of cycling lanes, create N to S and E to W express networks, and to provide continuity between Paris’ suburbs and the city. More cyclist friendly circulation rules are also being implemented. Traffic calming and “pacification” of public roads and public space in Paris began in 2008 and continues until today. Transformation of the city’s squares, like Place de Clichy and Republique have given back space formerly for cars to the pedestrian. By 2020, Place de la Bastille, Nation, Italie and Gambetta will be transformed to provide more space for active modes of transport.

Perhaps the most famous recent development has been the closure of the Seine Expressway, which has been turned into a pedestrian path for strolling, sport, and culture. There are further plans to redesign entire streets just for transit, emergency vehicles, walking, and cycling. To learn more about Paris’ Roads and Mobility Policy, check out this presentation by Christope Najdovski, Deputy Mayor of Paris for Transport.

Governance of Transport in Paris

There are three main levels to the institutional framework governing public transport in the Ile de France region. At the strategic level, the French national government and the EU set general objectives of public transport policy via laws and regulations. From there, things get muddy, where the national government governs Grand Paris and the regional authority Transport Syndicate of Ile de France (STIF) arranges transport services and necessary investment via concession contracts. To oversee maintenance, renovation, and extension of the existing network, the Transport Sydnicate of Ile de France (STIF) was created. Recently their name changed to Ile de France Mobilite, but their function remains the same. From there, operators deliver the objectives set by regional and national authorities. The major players are nationally-owned operators RATP (metro, tram, and buses) and SNCF (mainline, international, and regional trains), which carry 54 and 40 percent of public transport passenger kilometers in the region, respectively.

The biggest change in Paris’ regional governance of transport was adopted in 1994, after Paris had to be brought in line with a European scale once again and the Paris area developed beyond the confines of the Ile de France region. Polycentrism was confirmed with the assertion of new cities in the region becoming economic and logisitical hubs. This spread was accompanied by the boost in public transport and automobile networks. A durable funding mechanism based on the “benefiter-pays” principle levies a “versement transport” (a dedicated transport tax) on businesses with more than nine employees. As transport tax is a payroll tax, the amount collected is contingent upon the employment rate and on the amount of wages paid by companies. It is a dynamic source of funding but it is also very sensitive to the economic environment, as was the case in 2009 when receipts from the tax stagnated. This is a challenge in an because operating expenses tend to rise year on year. In this case, re-allocation of existing tax-based revenue on office space or increased government contributions can fill the gap. Overall, the innovative transport tax is relatively unique to France and could serve as a model to other cities needing new dedicated sources for transport funding.

For a paper going over more detail of the history and development of transport governance in Paris, this excellent article traces the shifting responsibilities of delivering transport in the Ile de France region.

Velib, Dockless Bikeshare, and the State of Cycling

Another reason to visit Paris was to learn about Europe’s largest bike share scheme, the Velib, with 1,800 stations and more than 20,000 bikes. The scheme was first implemented under Mayor Delanoe in 2007. The model is innovative in that the system operates as a public private partnership (PPP) between the city and JC Decaux, a family-owned and French-based advertising company. Seeing the success of this PPP in the French city of Lyon, this model was tested on a larger scale in Paris. The system had significantly larger geographical coverage and number of bicycles per inhabitant. With the Velib increasing the availability of bicycles for short trips in and around Paris, so too did the visibility of bicycles. Accompanying the system’s introduction came the planning of some 700 km of bicycle routes, 60% of which were built in 2014. Cities around the world looked to Paris to see an example of how to turn a relatively car-dominant city into one more friendly for cyclists.

However, upon my arrival in Paris, I noticed many docks were empty. The bikes I could find were run down or in disrepair. I spent a few hours on the first day trying to find a functional bike, walking from terminal to terminal. Confused, I did a quick search on Google and found out that the city had entered a contract with new operator Smovengo back in January 2018. The operator had experience with smaller cities in France but was untested at operating systems the size of Paris. In its concession, the company wanted to upgrade stations so as to provide e-bikes as well as regular bicycles. But poor management and trouble with electrifying some 1,460 stations has led to a bit of a mess. Smovengo has had to pay a string of fines for its failures, and there is talk of the city auditing the contract to take over operation of the service.

Thankfully I had my cousin’s bicycle to use, but not all Parisians have the luxury of owning a bicycle. To fill the gap, several dockless bikeshare and scooter sharing companies have seen the chaos with the Velib system as an opportunity to improve their market share. But these schemes have also had their troubles with vandalism and theft. It’s a shame to see such a famed bike share scheme suddenly turn to an eyesore for Paris. Mayor Hidalgo, who has championed sustainable transport in the city, has recently faced the overturning of the city’s pedestrianization of the road on the banks of Seine and Paris’ push to ban cars is looking embattled. In March, the mayor’s disapproval rating was 58 percent.

Visit to the OECD, International Transport Forum

Paris is also home to the headquarters of the OECD, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Within the OECD, the International Transport Forum (ITF) serves a think tank for transport policy issues within the lens of sustainable development, prosperity, social inclusion and the protection of human-life and well being. It is the only global body with a mandate for all modes of transport, and therefore was the perfect organization to visit. I was introduced to Philippe Crist, a senior economist and project manager at ITF, by his sister Isabelle, who works at Vanderbilt’s GEO office. She was pivotal in getting me to study abroad in Copenhagen back in 2016. It was there where I became enamored with studying urban mobility. It was an amazing coincidence that her brother Philippe works on international transport policy at ITF.

My conversation with Philippe spanned many topics. He highlighted ITF’s recent work on the impact of shared autonomous vehicles on traffic and curb space. His team’s analysis found that a whopping nine out of ten vehicles could be removed from city roads, and 6.5 out of ten vehicles would be removed at peak times. We also touched on distributed ledger technology and blockchain’s impact on 21st century transport. When we got to cycling, his enthusiasm and understanding of the societal benefits of health, traffic safety, and economy from cycling was unmatched. One of the studies he conducted found that the monetized benefits from improved health are up to 20 times greater than the combined health impacts of crashes and exposure to air pollution. It was a good statistic to hear, because I had cycled to the OECD earlier that day, behind a truck that was spewing black smoke. He recognized the challenge of overcoming automobile oriented city planning, particularly given his experience in Paris and the United States. Nonetheless, Philippe believes cycling is a fantastic way for cities to achieve sustainable mobility with relatively little investment, while also enhancing the health of its citizens. For his work, Philippe received the Danish Cycling Embassy’s Leadership in Cycling Promotion Award in 2016.

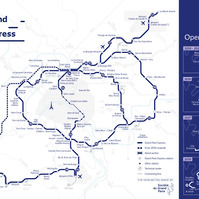

Grand Paris Express

Surpassing London’s Crossrail project as the largest infrastructure project in Europe, the Grand Paris is a wide-ranging development spanning the entire city. The project’s nature is twofold: to deliver a polycentric mass transit network as well as an urban planning project. The goal is to “improve living conditions for inhabitants, eliminate any inequalities between the various regions and districts, and build a sustainable city.” The project aims to forge local agreements between cities and the state to realize public infrastructures which will enhance economic development. The project was proposed by engineers to alleviate congestion in the central network, especially for suburb-surburb travel.

For a project of this size and scope, many stakeholders need to come together, including local citizens, businesses, and the many levels of government. The project presents a consistent roadmap and governance structure for modernizing and extending Paris's existing public transport network and creating new automated metro lines. These improvements to the transport infrastructure are driven by commitments from the State, the Île-de-France Region and the local departmental councils. The project's clients include RATP, SNCF, Société du Grand Paris, local authorities and STIF.

I visited the Fabrique du Metro near the Mairie de Saint-Ouen metro stop to learn more about the project’s development, and the extension of Line 14 from Saint-Lazare to the new station. In line with the goals of the Grand Paris Express, the extension will relieve congestion on Line 13 for its 680,000 daily users. The fully automated line will feature an average speed of 40 km/h instead of 25 km/h for a conventional metro line, with one train every 85 seconds during rush hour. The project is another example of transit-oriented development, with new housing stock being built between the Clichy-Batignolles and Docks de Saint-Ouen districts. With four new stations serving the 17th arrondissement, Clichy-la-Garenne and Saint-Ouen, line 14 will help drive the development of the 96,000 inhabitants and 72,000 jobs in the North-West Métro area.

Building Better Around Transport Infrastructure

The Jourdan - Corentin - Issoire Workshops

This building is an example of one of the ways Paris is reinventing new forms of housing architecture. The Jourdan-Corentin-Issoire development was completed in 2017 and involved a set of 650 social, private and student housing on top of a RATP bus depot. This piece of city occupies a plot of 1.7 hectares bordered by the Boulevard Jourdan, the Rue de la Tombe-Issoire and Rue du Père Corentin. RATP, the public transport operator in Paris, has several bus depots that needed to be modernized and expanded. Given the relative scarcity of large plots of land in Paris, the solution found was to reconstruction in the basement on several levels. The sale of land to real estate programs on the surface made it possible to finance the project, which involved digging new levels and reconstructing in the substructure. At the same time that RATP's bus depot was modernized, new housing units were created. There are plans for more than 2,000 housing units in Paris by 2024 as part of the restructuring of RATP’s Parisian industrial sites.This kind of mixed-use development around transport infrastructure shows promise in sustainable ways of building cities in the future.

Buildings for Automobiles

At the end of the 19th century, Paris became a hub for the automotive revolution. The rapid spread of the automobile was accompanied by new kinds of construction designed specifically for its use. Today now that less than 35% of Parisian households own a car, these parking structures are clearing out. I visited an exhibition at the Pavillion de l'Arsenal, Paris' architecture and planning society, which describes and envisions possible changes to these structures. The potential to reprogram these old structures, rather than demolish them, will allow the city to transform infrastructure that is already there.

Parting Thoughts

Paris was a dynamic and exciting city to visit. The city's history of being at the forefront of innovative mobility solutions is evident, especially since past obsessions with car-centric planning have led it to make more radical changes in active mobility and public transport over the past few years. I was lucky to be in town during the height of World Cup fever and Bastille Day. I watched the semi-final and final along with millions of Parisians. In celebration, people climbed on bus stops, flooded the streets, and proudly waved the French flag. These are memories I won't soon forget.