Hiroshima (and Onomichi, Osaka, and Kyoto)

October 27-November 2

After a 14 hour flight from Los Angeles to Tokyo, I was tired to say the least. I spent an evening in a hostel and collected my Japan Rail Pass, a comprehensive ticket to all Japan Railways Group companies in Japan. This ticket offers access to most of the Shikansen "bullet trains" and is a great way to hop from cities in Japan in comfort and ease. I chose the seven pass for my thirteen day stay in Japan. As such, I traveled to many cities in these seven days to maximize value of the pass. I visited the most popular cities on the island of Honshu: Hiroshima, Osaka, and Kyoto. But first, I had the opportunity to take part in a world-class cycling event in Onomichi.

Onomichi

October 27-29

My first venture into the Land of the Rising Sun began with a sprint from Tokyo towards Hiroshima. With my Japan Rail Pass in hand, I took the world famous Tokaido Shikansen "bullet train" from Tokyo towards Onomichi. I was heading to this part of the country to take part in the Shimanami Kaido Cycling Event. The 70 kilometer route (see map below) connects the mainland island of Honshu with Shikoku through different little islands on the Seto Inland Sea. I was stunned by the natual beauty and scenery along the route; seven modern suspension bridges took more than 7,000 riders across the islands. I found the course a fantastic introduction to Japan (and a good way to beat jet lag too)!

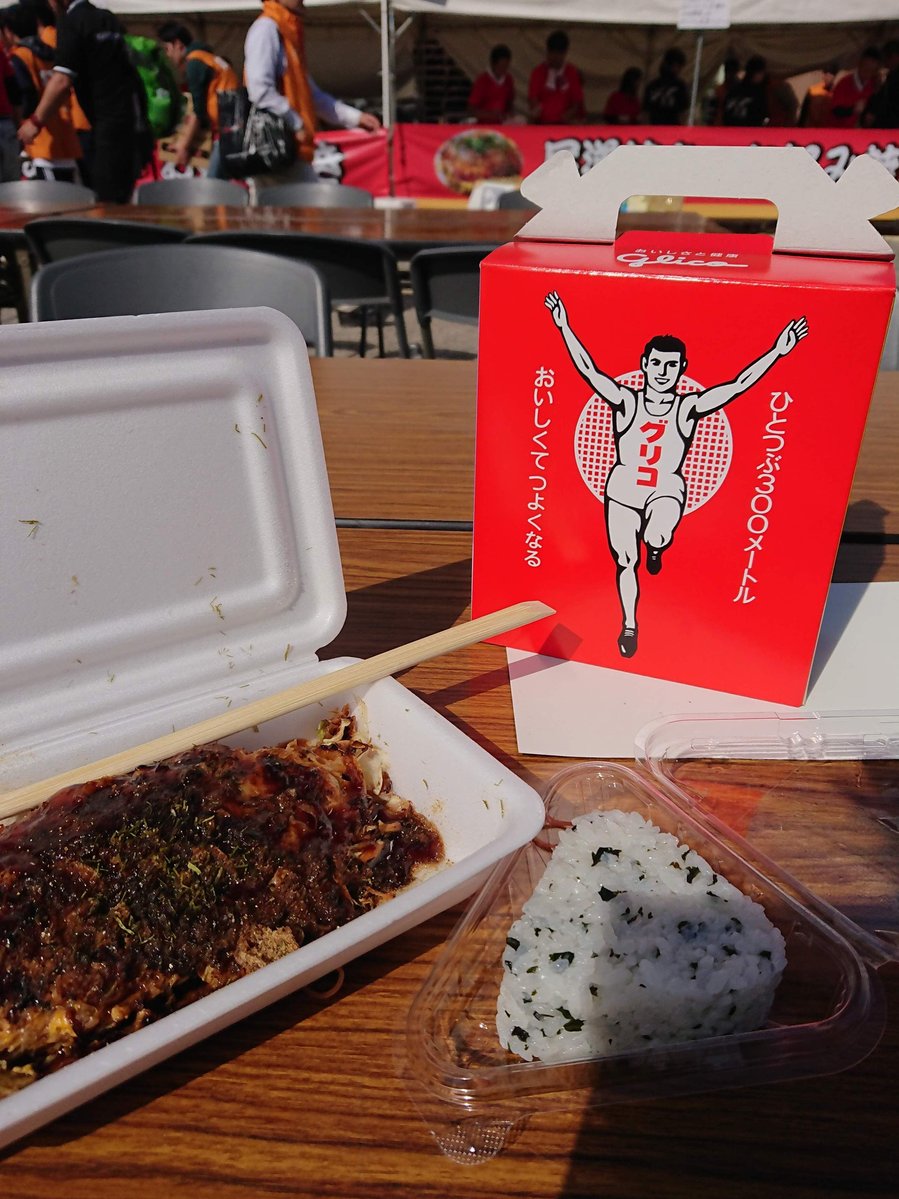

Rest stops offered opportunity for unique Japanese refreshments. Delicious energy-boosting lemon jelly, bananas, and bread kept me going during the four-hour long trip. I was thrilled to find out that upon arrival at the finish line, Okonomiyaki was served. The dish is a kind of savory pancake containing any number of ingredients. In Japan, the title of best Okonomiyaki is hotly contested between the cities of Hiroshima and Osaka. I tried both versions, and found the Hiroshima-Style Okonomiyaki better because ingredients are layered (rather than mixed) and featured delicious udon noodles in the center.

Hiroshima

October 29-31

City in Context

Context for city development in Hiroshima begins on the morning of August 6th, 1945. At 8:15 am, the US B-29 bomber Enola Gay released Little Boy, a 16-kiloton atomic bomb. Within half an hour of the bomb dropping, almost every building within a two-kilometer radius of the explosion was in flames. About 90% of the city’s 76,000 buildings were partially or totally incinerated, or reduced to rubble. Of the 33m square meters of land considered usable before the attack, 40% was reduced to ashes. I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial museum on Monday morning to learn more about the horrors the citizens of Hiroshima experienced. Afterwards I went to the Children's Peace Memorial and the Atomic Bomb Dome to pay respects to the victims of the bombing.

Once Japan had surrendered on 15 August 1945, local authorities in Hiroshima had the enormous task of reconstructing the city. Factories previously in service to aid the war effort could now be used to raise production for services that would restore the city to the industrial powerhouse before the bomb fell. The city drew up a five-year recovery plan to accomplish this goal, but struggled with fiscal constraints caused by an 80% decline in pre-bomb tax revenue.

In 1949, the national government of Japan passed the Peace Memorial City Construction Law, which states that “Hiroshima is to be a peace memorial city symbolizing the human idea of the sincere pursuit of genuine and lasting peace.” The law also opened new sources of tax revenue to city planners and resolved questions of land ownership. Japan’s postwar economic boom in the 50s spurred construction,and by 1958, Hiroshima’s population returned to its pre-war level of 410,000.

One of the major points of contention in development of the city after the war was whether or not to preserve Hiroshima’s tragic history. Some officials favored removing painful reminders of suffering after the bomb fell.But in the end, locals and stakeholders favored historical preservation, as evidenced by the remains of the former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, also known as the A-bomb Dome. This monument became an icon for the city, and can be visible in a straight line from the cenotaph commemorating the victims.

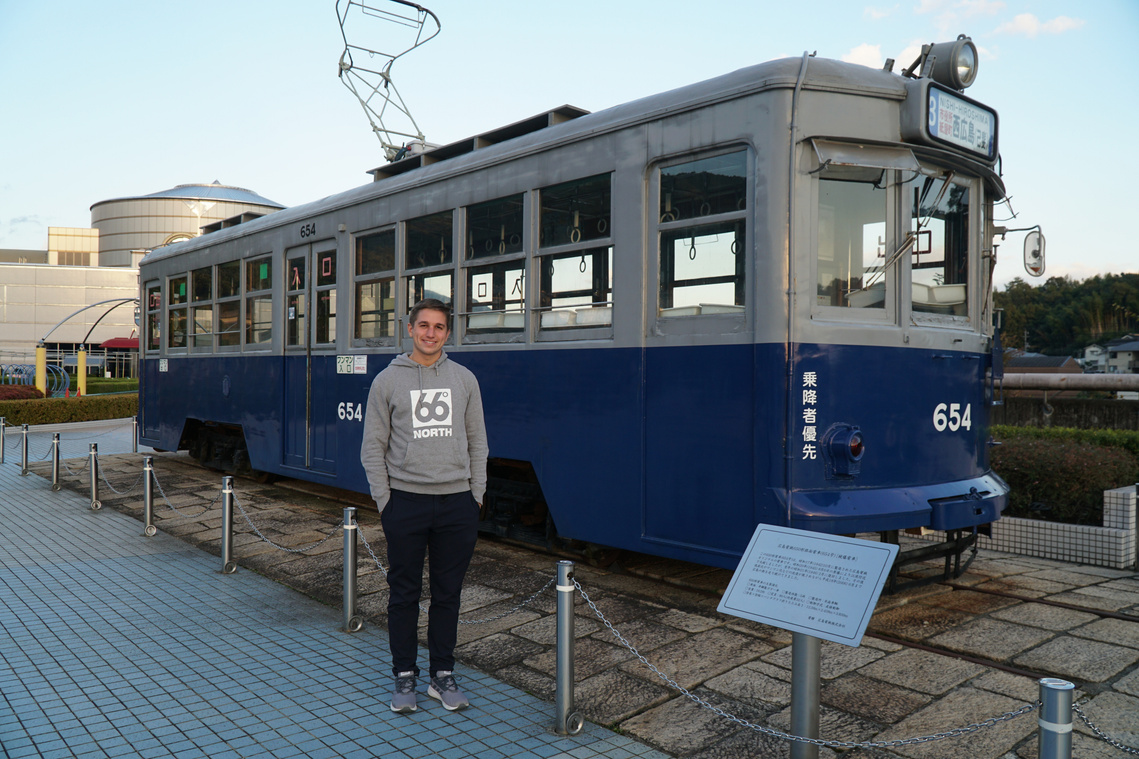

Today, the A-bomb Dome, Peace Park and a few preserved buildings are the only architectural reminders of the attack. The tram network that predated the bomb has been restored. The city that has grown around these reminders of Hiroshima’s suffering has features common in many cities throughout Japan:office and apartment blocks, neon-lights and attention-grabbing advertisements,convenience stores and coffee shops. Visiting the city offered an interesting perspective to explore the dilemma of how to incorporate the city’s tragic history with its post-war reincarnation.

Hiroshima’s Iconic Tram Network

Trams are considered by many residents in Hiroshima to be vital to the lifeblood of the city’s urban transportation network. The tram system’s roots can be traced back to 1910 and aided in the development of a rapidly industrializing city. After the bomb fell, transport services scrambled to restore service to aid in recovery efforts. With the need to move people and supplies into the city growing more urgent by the hour, the Ujina railway line started moving again on 7 August; a day later, trains on the Sanyo Line started running the short distance between Hiroshima and Yokogawa stations. The tram network resumed a limited street car on 9 August, three days after the bomb had fallen on the city.

Today, the tram network has been restored to its former glory, and has become one of Japan’s busiest tramways. Hiroshima Electric Railway (HER) is the private company that operates the city’s 600-Vdc network of 19.0 km of tramways and 16.1 km of light rail. The total fleet of vehicles numbers in 267 carriages (108 tramcars and 159 light rail vehicles). Like San Francisco’s tram fleet, the cars originate from various cities besides Hiroshima. Some cars were inherited from systems in Hannover and Dortmund in Germany. Others are heritage trams that were restored after the atomic bomb devastated the city in 1945 (two from that era are still in operation today). In terms of modern new vehicles, HER has introduced some ultra-low-floor light rail vehicles (dubbed Green Movers, see below) in an effort to make the tramway more accessible for the elderly and disabled.

When I was in Hiroshima, I took one of the tram lines to the ferry terminal to Miyajima Island. The light rail line provides through connections on the urban tram network, offering convenient transit options for some suburban residents. When I got on the ferry, I had the pleasure to witness Itsukushima Shrine. The attraction is home to one of the more surreal scenes in Japan: a massive Tori gate that seems to float on the water. With trams and a ferry, I was able to access this spot merely 30 minutes from Hiroshima main station!

Rural Mobilities in Japan: Tackling the issue of Depopulation and an Aging Population - Jenny Yamamoto

During my stay in Hiroshima, I was fortunate to be hosted by Jenny Yamamoto. Born in Japan to a British father and a Japanese mother, Jenny comes from an international background and has lived in Tokyo and London. She is a PhD candidate at Hiroshima University and previously worked in the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) in Bangkok. Itwas there where my father and Jenny met one another. More than 20 years later,Jenny’s path and mine crossed in Hiroshima.

I was especially keen to speak with Jenny given her area of expertise on rural mobilities in Japan and abroad. Despite my focus of research for this fellowship concentrating on urban mobility, I had never thought much about rural passenger transport in the manner which Jenny told me about. She provided invaluable insight into the case of rural mobility in Japan, especially in the context of a rapidly aging population.

The root of much of the problems facing rural mobility systems in Japan is that the population is shrinking. The 2015 national census results confirmed that the national population declined by nearly one million people since the last census in 2010. By 2030, the country is expected to lose one million people per year due to depopulation. This decline is acutely felt in rural areas. A government-appointed commission released a report in 2014 containing future population projections for all of Japan’s 1700 municipalities. Astonishingly,900 were labeled “cities at risk of extinction,” meaning that the population of child-bearing age women is expected to decline by more than half by 2040. The hardest-hit regions are in the rural and isolated mountains of central Kyushu,western Honshu, and the Kii Peninsula, and the entire northeast Tohoku and Hokkaido regions.

For transport in these areas, the depopulation effect has led to local public transportation operators withdrawing services from routes. The number of trains/buses per day and other indicators of level of service continue to decline drastically, and private operators who provide local transportation services find it harder and harder to run profitable businesses. The statistics show that roughly 7,509 km of local bus routes were completely eliminated in the six years from FY2010 to FY2015, and 37 railways (roughly 754 km) became defunct in the 15 years from FY2000 to FY2015.

These declines are partially the result of large-scale liberalization of transportation policy at the start of the 21st century. Liberalization also applied to regional public transport such as railways and buses, and restrictions regulating supply and demand were eliminated. Restrictions on ending operations along a certain line were similarly reduced to allow closure only by advance notice. This privatized approach to transport delivery in Japan has worked well in major urban areas, but leaves a real dilemma when it comes to providing a level of service necessary for sustainable transportation systems in regional Japan.

The liberalization of the Japanese public transportation market had the effect of reducing mobility for residents who cannot afford to use personal automobiles. TV programs even showed sensational scenes of elderly people with advanced dementia driving to the hospital. With a clear need for government intervention and an increased concern about the crisis in daily transport for Japan’s aging population, the Act on Revitalization and Rehabilitation of Local Public Transportation Systems was passed in October 2007.

Based on the Revitalization Act, municipalities can prepare a comprehensive cooperation plan for local public transportation systems, after consultations with statutory councils comprising relevant public transportation operators, road administrators, public safety commissions and users. Then, they submit the plan to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Japan’s governing body for transport. Public transportation businesses positioned in the comprehensive cooperation plan certified by the ministry are then given preferential support measures under relevant laws are taken to subsidize operations.

As the environment surrounding local public transportation systems grew increasingly severe, it became necessary to support local public transportation businesses through partnership between local residents, governments and business operators as well. Partly against this background, the Basic Act on Transportation Policy was enacted in December 2013. The Basic Act, under “the basic recognition that it is important to appropriately satisfy the basic transportation demands of the people and other persons,” set out the fundamental principles of transportation policies,responsibilities of the state and local governments, responsibilities and roles of transportation-related businesses and the public in cooperating with transportation policies, and coordination and cooperation among relevant parties. The Basic Act further states that the Government must establish a basic plan on transportation policies, the Basic Plan on Transportation Policy,which sets forth the basic direction of transportation policies, their targets and measures on transportation that the Government shall implement. This is similar to a SUMP model discussed in my travels to European cities, where local governments prepare plans to deliver sustainable local public transportation networks for citizens.

While the policy is now in place for city governments to take control of their own transport in Japan, Jenny lamented that many local governments lack the experience and ability in implementing local public transport policies, and there are insufficient local government financial resources to support them. Local initiatives like community buses and rideshare taxis are steps in the right direction, but lack the coordination and capital required to make real improvements to levels of service for residents of smaller cities. I think Japan could look closer at other countries to find methods for procuring public funds for improving local transport, like a dedicated “versement transport” business tax in Paris.Whatever tax instrument local governments choose to use, the money must be spent in a manner that keeps students and the elderly in mind, and keeps Japan on the right track in terms of sustainable urban transport systems.

Read more:

1. Community Development and Local Public Transportation Systems – Shunsuke Kimura

Osaka and Kyoto

October 31-November 2

My stay in the cities of Osaka and Kyoto was short but sweet. I was only able to do some sightseeing in these cities to maximize the value of my JR pass. For Osaka, I found this link that details the city's fantastic efforts to become a world class cycling city. The following photos include some highlights from my two days in these two cities.