Last Thursday, the American government released their proposed federal budget, confirming many of artist’s most dire speculations. The budget proposes to eliminate funding for 19 agencies in favor of increased defense spending and a down payment for a wall at the Mexican border. The arts and humanities are among the casualties.

Confirming months of rumors, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is on the table for being scrapped entirely. Apocalyptic mood music. Thoughts of armageddon. Tangential thoughts about art under fascism. No NEA means a totally privatized art world. What will this look like? Here we take a look back at the NEA’s history, and unpack what it’s death could mean.

First let’s zoom out. The NEA has existed since 1965 as the official US bureau dedicated to fiscally supporting the arts. It’s an agency that has supported the likes of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe and poet Annie Dillard, and has provided thousands of grants to literary, musical, performance and visual art endeavors over the past fifty years.

For as long as it has existed, the NEA has caused controversy over government spending. Its history is that of a (belligerent) game of tug-of-war between conservatives and liberals, the former of which have historically attacked it for representing “liberal elitism” fuelled by big government spending, as well as for supporting “anti-Christian” cultural production.

In 1989, when the Corcoran Gallery opened a show featuring Robert Mapplethorpe’s photography — which included images of flowers and homoerotic portrayals — North Carolina Senator Jesse Helmes proposed a ban on all national funding for art that depicted sexually explicit or non-Christian (gay) images. Though this specific proposition didn’t get pushed through, Helmes set the precedent for what would be two ensuing decades of conservatives lambasting the NEA. Interestingly enough, Reagan never directly attacked the NEA (he initially entered into his presidency with intentions to slash it, but soon reneged on this).

In 1981, Reagan appointed a presidential Task Force to bring more private groups and individuals into the NEA decision making process. Read: Reagan made it his business to strengthen ties between the NEA and cultural philanthropists. This detail about Reagan is worth mentioning, because it illustrates the fallacy of the “liberal elitism” charge against the NEA. Only under our most conservative administrations has the NEA been deeply tied up with cultural philanthropy (which does indeed introduce elitism into artistic production, in that it gives funding jurisdiction to enormously wealthy donors).

Throughout the 1980s, the NEA continued to be used as an arena to joust over ethical questions about the scope of government. Prominent Christian media figures and conservative senators led a war cry against the NEA in the late eighties, spurred by incidences like the “un-Christian” Robert Mapplethorpe exhibit. The NEA became a battleground for principles, with little to no regard given to the reality, which was that the NEA was a relatively centrist organization committed to expanding cultural, artistic and educational opportunities for marginalized groups in both urban and rural settings.

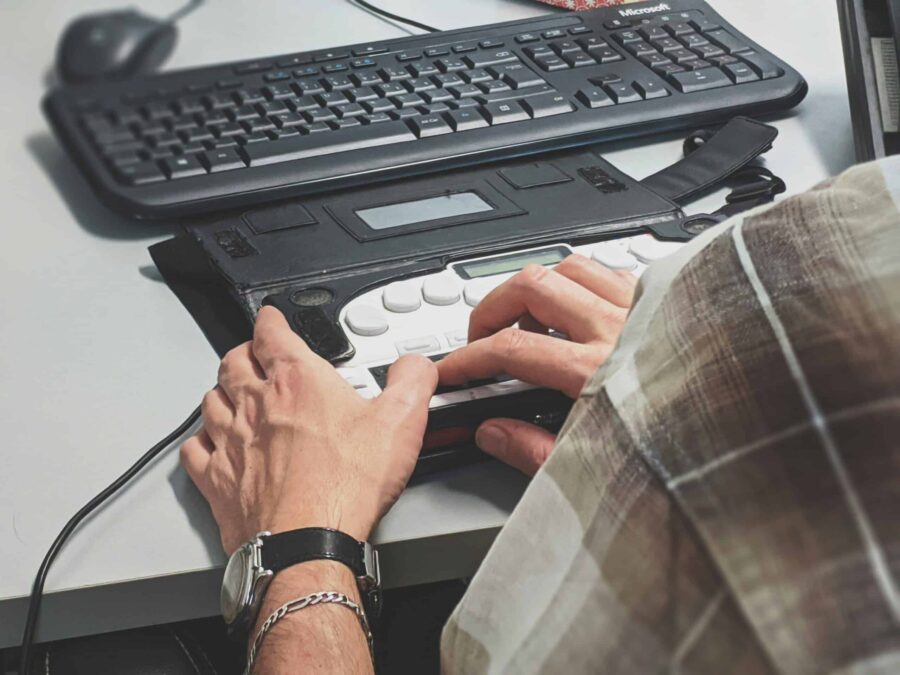

A snapshot of some of the NEA’s early work gives a sense of its ethos. In 1967, the NEA rolled out the Audience Development Project, an initiative developed to fund concert series for young and unknown artists. In 1978, the NEA began to liaison with the office of minority concerns to establish specific funding for minority art groups and artists. In 1988, the NEA began a process of collaborating with state education agencies to make the arts a basic necessity in early public education. In 1989, the NEA began a Rural Arts initiative to strengthen rural arts organizations. In 1994, the NEA produced a guide for endowment grantees and others for making programs and facilities fully accessible for people with disabilities and for older adults. This is but a slice of the NEA’s historical activities, but it’s enough to illuminate the absurdity of the claim that the NEA has somehow promulgated elitism.

In spite of this, the 1990s saw house speaker Newt Gingrich lead a renewed attack against the NEA, again with the charge that the NEA was an appendage of liberal elitism. And the notion—however fallacious—has stuck. What we’re seeing today (in our aptly coined “post-truth” society) is a renewal of Gingrich style NEA berating coming from our current administration and its associated media machine. In an article recently run by Fox News, the fundamental misrepresentation of the NEA’s ethos continued.

“Subsidies pay for art rich people like. Like so many other programs, government arts funding is a way for the well-connected to reap benefits while pretending to help the common man,” writes Fox reporter John Stossel. “Government arts funding doesn’t even go to the needy”.

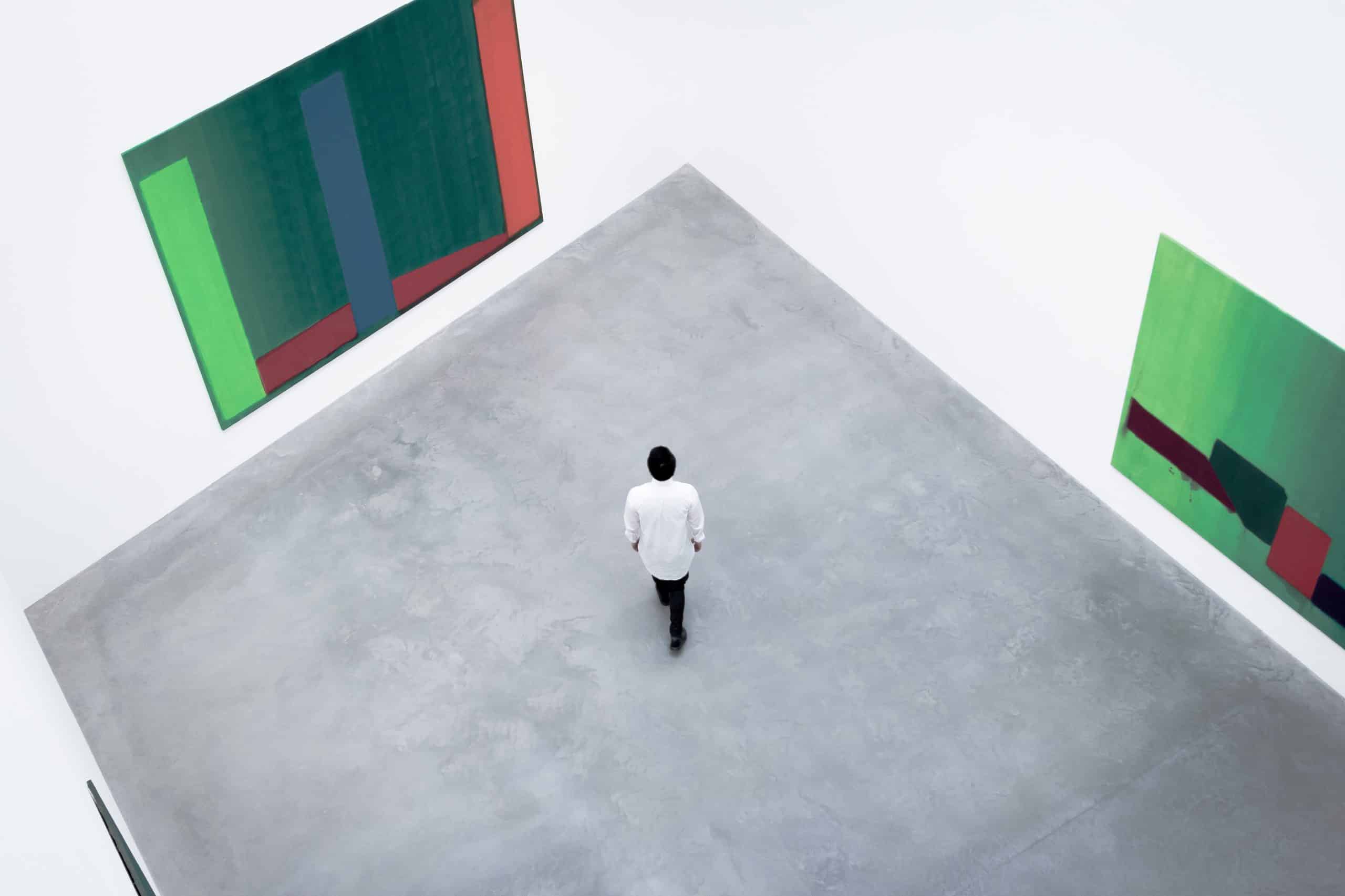

Quite the contrary Mr. Stossel. With every slash to the NEA, we have seen a rise in what art critic Nato Thompson refers to as “the nonprofit industrial complex” in his book Seeing Power: Art and Activism in the 21st Century. This idea describes the state of nonprofits becoming increasingly dependent on the whims of wealthy donors in order to stay afloat. What this means: there is a necessity for arts organizations to display and disseminate art that is acceptable to the wealthy. There is a chilling effect, wherein artists and organization are unable to freely produce content or ideas that may perhaps challenge capitalist structures, for fear of alienating their wealthy patrons. This points towards a future where art and cultural production will have to toe a narrow set of ideologies: propaganda of the free market.

Starting to see the irony? It’s not government funded art that begets “elitism” in the art world. Rather it’s privatized funding. Without public funding, nonprofits will essentially have to parrot the ideology of their donors. And they’ll have to have access to those donors in the first place. See where we’re going with this? Access to private donors is a lot easier to get when you have an expensive academic badge or a pre-established network of people to tap into. Although the NEA has never historically been a handsomely funded government body, it has predominantly functioned as a helping hand for organizations that are hard pressed to tap into this sort of network. So, as with many of the cuts associated with Trump’s new budget, those who are already most vulnerable are set to be hit the hardest.

Across the country, culture workers and activists are responding with ire, and gearing up to protest. America for the Arts is mobilizing thousands of local councils and agencies to flood congress with calls and petitions.

In Seeing Power, Nato Thompson aptly foreshadows our current quagmire:

“All in all, privatization has constrained and contained the variety of infrastructures of resonance available to all of us, thus forcing each participant to scramble for the scraps. Privatization hasn’t simply scaled back (and in many cases eliminated) benefits for the middle and lower classes—it has also placed increasingly conservative pressure on the forces that produce our sense of self.”

With this quote, Thompson gets at one of the scariest reverberations this cutback is poised to set in motion. Our sense of self, values, and desires are formed by the culture we navigate everyday. Non-profits and arts organizations play a large part in our collective identity-formation. With the rise of the non-profit industrial complex, we are being exposed to narrower and narrower sets of ideas.

Moreover, it goes without saying that some of the most socially engaged art doesn’t really turn a profit, because that’s not necessarily what it has been created to do. Without reliable government funding, these more ideological art organizations are going to have reimagine themselves to be driven by a bottom line instead of by a mission. Welcome to the free market.