Sewing pom-poms onto a lycra bodysuit while on the phone to a foundry in China might not sound like your usual 9 to 5. It might not even sound like an on-the-side freelancing gig. But it’s a situation that most artist assistants wouldn’t raise their eyebrows at. Doing offbeat tasks have almost become the norm for the hundreds of grad students and young artists who work for other artists.

While little is known about the role of artist assistant, and vacancies are usually never publicly advertised, it’s a highly sought-after position. For anyone looking to gain insight into how a large-scale studio operates, assisting an artist can provide invaluable training. Working as an art assistant can also boost the career of an emerging artist, give them access to high profile contacts and high quality materials, and help set the foundations for their own blossoming art practice.

But working as an art assistant can also be a thankless and monotonous job. It could involve coloring in prints of Gilbert & George’s genitals for eight hours a day, as Jake and Dino Chapman did; painting thousands of colored dots for Damien Hirst like Rachel Howard; or working on the same piece over five months, only to have it binned by Jeff Koons and told to start over, as painter John Powers experienced. It’s hard work by anyone’s standards.

Not only is an artist assistant expected to possess a wide skill set, work odd hours, be extremely discreet, efficient, expert at solving problems, manage the portfolio website and juggle multiple projects at once, they receive no recognition for the pieces they make, earn low salaries and usually aren’t entitled to sick days or vacation pay.

We decided to look behind the smoke and mirrors of the art world and find out what it’s really like being an artist assistant. Amy Houmøller, assistant to Ryan Gander for a little over a year, tells us about her experience working for one of the freshest names in contemporary British art, and her advice for someone wanting to start as an assistant themselves (hint: networking helps).

Format Magazine: Hi Amy! So, you worked for Ryan Gander for a year. How did you get that position?

Amy Houmøller: It was essentially through people I know. I had previously worked at Lisson Gallery and had got to know him a little there. I was working at Frieze and a friend told me he was looking for an assistant so I emailed him to ask about it… and the rest is history!

What made you want to work for Ryan? Where you attracted purely to his aesthetic, or did you start working for him for other reasons?

I didn’t deliberately seek out an artist and decide I wanted to work for them, but there was an element of wanting to work for someone respected, and whose practice was very varied, which would mean a more interesting working environment. I also knew he was a nice guy, which I am quite sure not every artist is! I’d also explored quite a lot of the art world and was yet to work in a proper artist’s studio, so wanted to add that string to my bow.

What’s your background? Did you go to art school?

I dropped out of art school and changed to art history, then did a masters in Curating and Contemporary Art Theory. But I’ve always continued to make work, so have some practical skills which I knew could be applied to this role. Before this job I worked as an assistant to a photographer, a manager of a small gallery, artist liaison assistant at Lisson and then at Frieze.

I think for most people outside of the art world, the role of artist assistant is very mysterious, and maybe only became known to the general public thanks to the huge art factories of Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons. What’s a common misconception people have about this role?

A lot of people asked what on earth I did all day in the role. I think they imagine a studio full of people angle grinding and welding, while the artist sits on a throne smoking a cigar. It was actually a lot like any other job, in that everyone spent a lot of time coordinating, working on timelines and getting things ready for deadlines, including Ryan. And while some works were made on site, an awful lot are made at foundries, etcetera, which requires quite a lot of admin.

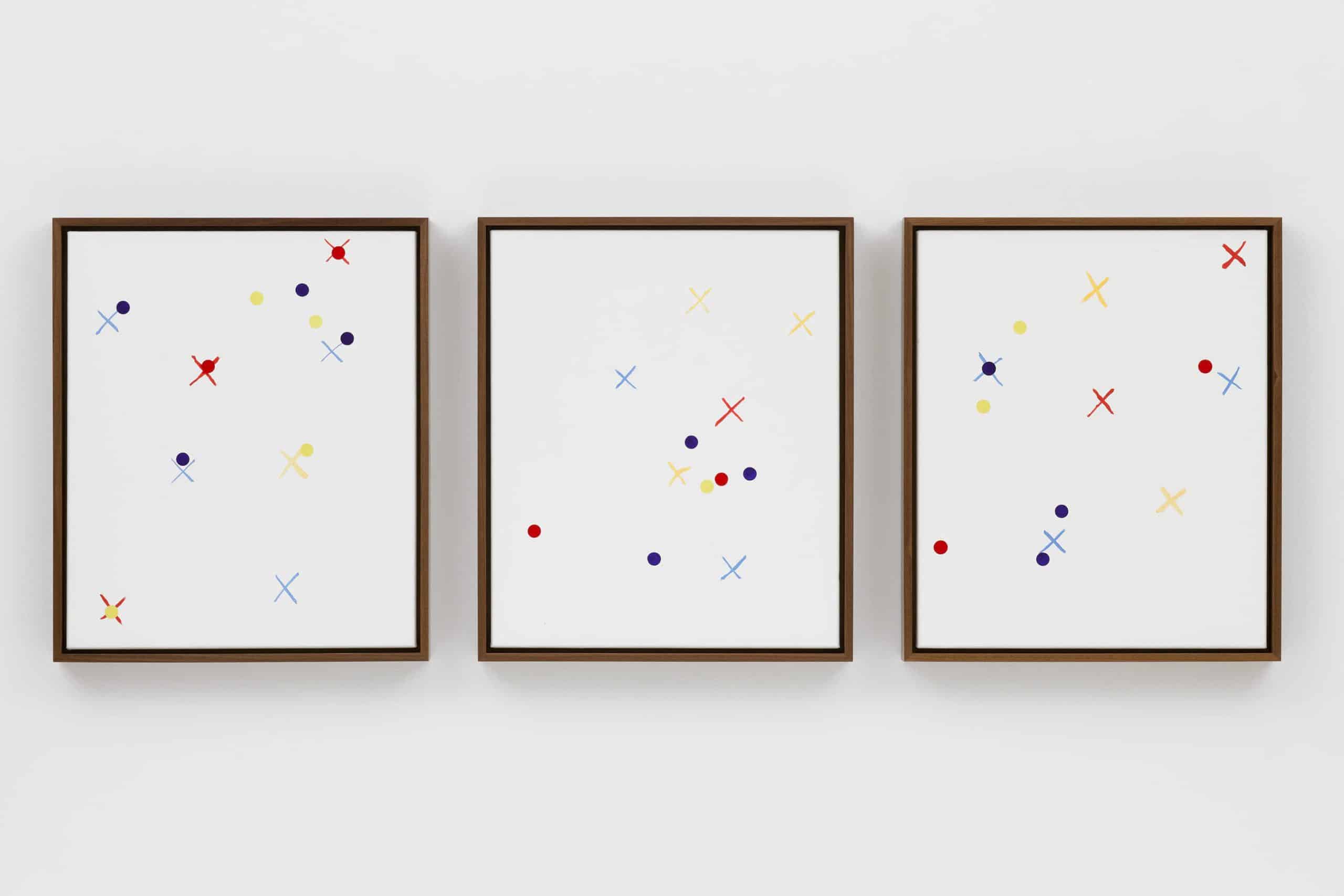

A toppled Breuer chair after a blizzard of snow (2017) by Ryan Gander.

Image via the 21st Biennale of Sydney.

Sure, there would’ve been mundane tasks to do too. What would your typical day-to-day at work look like?

Like all good art world jobs you started at 10 and no earlier! My job involved coordinating his diary, forthcoming shows and production deadlines, ensuring the team of about eight (spread over two different sites—London and Suffolk) knew where they were meant to be, as well as leading production for the large scale public works and commissions. Others in the team worked on other specific projects and had their own specialities, but it’s a small team so there was a lot of crossover.

Every day involved a bit of the same stuff—monitoring his emails and calendar, booking travel, but then things could vary wildly depending on what projects you were working on. I might be talking about marine grade steel on the phone to a Chinese foundry while sewing pom-poms onto a full-spandex bodysuit.

That actually sounds quite difficult! Were there any other days that weren’t so normal? And more specifically, what’s the weirdest thing you had to do on the job?

There were lots of fun and unusual things involved in the job. Sometimes I would have to research into odd things with very vague instructions, like ‘Find me all the objects invented in the north of England that emit light,’ or ‘I need a life size ceramic leopard today.’

Were there any times that you thought “I can’t believe I’m getting paid to do this”?

In my first month of working there I went to Japan with him for three weeks to film a BBC documentary. It was amazing, and I really couldn’t believe I was getting to see some rare and special things all around Japan; not just for free, but getting paid to do to. A lot of my travel with Ryan was based on his needs as a wheelchair user, though, so I’m not sure other artist assistants get so lucky.

Can we talk a bit about some of the challenges during the job—were there any times when you thought “I can’t believe I’m not getting paid more to do this”?

I was lucky—as Ryan runs an amazing team, it was supportive and fun. And they specifically employ people who will fit in. That said, like any job there were annoying things—sometimes after doing very fun and creative things, managing a diary seemed very tedious, and getting a creative person whose brain is going 100 miles an hour to concentrate and to listen to you, and to give you the answers you need, can be challenging!

Were there any kickbacks from working with Ryan? Did you get the chance to make your own work on the side, or have access to the studio when you wanted—to tools and materials?

I got to use his studio after work, yes, which was great, because at the time I didn’t have my own. He was also generous with contacts, and creating fun for the team. We cooked lunch for each other every day, which was a joy.

Houmøller (center) in Japan with Ryan Gander (third from left).

Can we talk frankly—was the pay worth it? Or was it somehow a kind of labor of love?

I got offered the job before they told me the pay, and afterwards I managed to up it a bit. The pay was fine… not amazing, but it was a great job, so you’ve got to weigh that up. At the time I took the job with Ryan I was also offered another role managing an artist’s studio which was £15k more per year. But some people who had previously worked with said artist told me it would not be worth it, and that nobody could stay in that job for long, as they were so awful. I chose to be poorer but happier. It depends on what you want and what you’re willing to accept at work, behavior-wise. That said, it’s art, and people will generally pay the bare minimum that they can get away with!

Working with anybody on a creative project can be very intense and intimate. What was it like for you in this position, personally speaking?

As I said, I was lucky that I got on really well with Ryan and the team. Travelling a lot with someone can be pretty intense though, and it’s definitely your job to be the peppy, organized and supportive one when you’re making work in some weird museum in a provincial German town or something! It was important to be honest and admit a screw up when it happened.

If I can ask about your reasons for leaving—was it always limited to a certain time, did you burn out, or were you offered something else?

It was a maternity cover contract. The previous assistant didn’t end up coming back after all, but the role was moved to the studio in the countryside where Ryan is spending more and more time, and I’m not ready to retire to the country just yet! Otherwise I would definitely have stayed.

If you could give advice to your younger self before starting the job, what would you say?

Actually, this question is more relevant to jobs I had before working for Ryan—working for him taught me that respect across all levels in a company, both up and down, should be a given, and that fostering a collaborative and non-competitive environment helps get the most out of people.

What about some advice to other graduates or young artists who are looking to become an artist’s assistant? Where should they look if they are after this kind of job?

Get to know people. Unfortunately that does help—not just schmoozing, but I’ve got a good network of friends I’ve built up through various jobs and we all help each other out with jobs and contacts. Lots of artists take interns too (and the good ones pay), and I know the lady whose maternity cover I did, who started as his intern. I also got to know Ryan doing reception part-time at Lisson, so putting yourself in a boring job can actually help a bit! And don’t expect it to be glamorous, sadly, at least for quite a while.

Cover image: Ryan Gander’s Key performance indicator i-iii, image via Lisson Gallery.

More reading on creative careers:

Photojournalist Emily Garthwaite Sees Photography as Therapy

The Jealous Curator’s Advice for Beating Creative Block

What it’s Like to Land an All-Expenses-Paid Adobe Residency