Making art is hard enough, let alone trying to make living off it. A recent survey of 2,000 artists by the Kickstarter-backed publication Creative Independent revealed that 29 percent of respondents relied on money from a family inheritance to support themselves. The same survey showed that even those artists who had gallery representation didn’t make much of an income from the gallery. As many as 42 percent relied on a day job to support themselves.

This is where services like Patreon come in. Founded in 2013, Patreon is an online platform designed to help creators get paid for making art. Currently used by about 100,000 creators, Patreon operates on a similar concept to Kickstarter—but instead of supporting a specific project by an artist, you directly support the artist. Ideally, the service functions similarly to the free room and board offered by royal patrons of centuries past, paying for the necessities of life so that artists are free to focus on their art.

Here’s how it works if you’re an artist. You set up a free Patreon account, creating a page that details who you are, what you do, and explains why people should finance your art, including different levels of support. Let’s say you offer access to exclusive artworks for $1 a month. You share this page with your many thousands of fans on social media. About a hundred of them decide to subscribe. Now your bank account is $100 heavier each month (minus a 5% Patreon fee and additional payment processing fees deducted by the service).

At least, this is the premise of Patreon. What if you have just 1500 Instagram followers, though, not 150,000? The possibility of “predictable income” and “a meaningful revenue stream” Patreon offers on its homepage is appealing. But is there any value in Patreon for creators who aren’t already kind of famous?

A quick browse through Patreon reveals a selection of the site’s “Top 20″ creators, grouped into mostly creative categories like Writing, Comics, and Photography. I had a tough time coming across brand new or emerging creators on the site, because Patreon doesn’t make it easy to find them. “We are not solving the ‘you don’t have any fans, to having fans’ problem—we’re solving how you go from fans to patrons, and building that sustainable income,” Patreon’s Head of Marketing, Carla Borsoi, told me in a phone call. Patreon wasn’t able to share how many patrons a user typically has, but I tallied up the numbers on a few of the more arts-oriented Top 20 categories (Video & Film, Comics, Crafts & DIY, Drawing & Painting, and Photography) and found that the average creator from these categories had about 2,000 patrons. These creators are raking in an average minimum of $2000/month, and perhaps much more if they have a lot of patrons subscribed to higher payment tiers.

I reached out to several of these Top 20 people to ask them about their experience with Patreon—why they decided to start using the platform, whether or not they would recommend it to other artists, how they went about finding patrons.

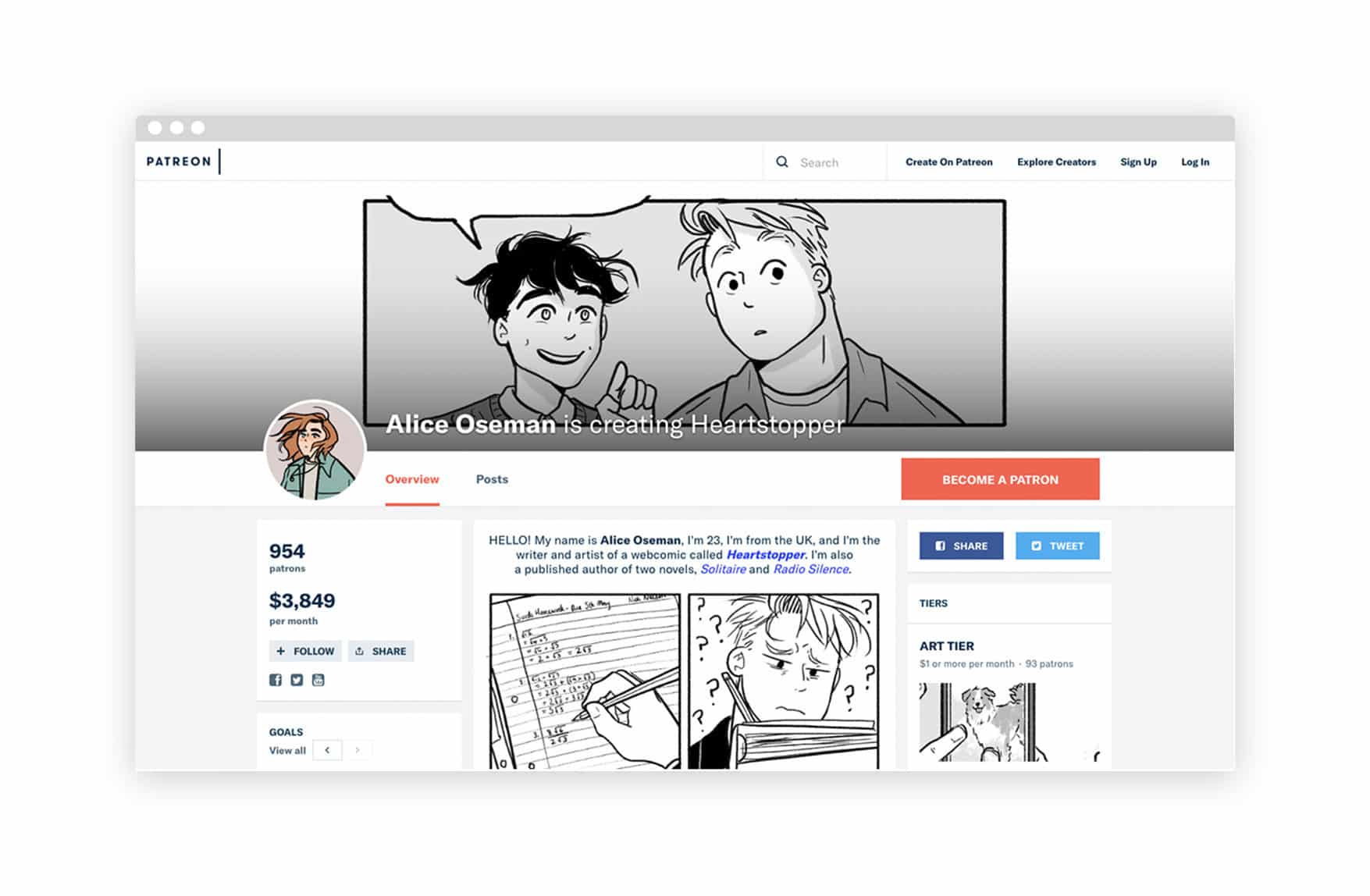

Alice Oseman’s Patreon page

Many of these creators told me that Patreon had improved their financial stability. Alice Oseman, who is currently making $3,849 monthly from 954 patrons, calls Patreon her “most regular and reliable source of income.” The 23-year-old writer and artist initially turned to Patreon in late 2016 as a place to promote her self-published web comic Heartstopper. “As I create and post the web comic entirely for free, it was a great way for people to support the comic financially so that I could dedicate more time to it and post updates more regularly,” she told me in an email. Oseman’s patrons receive early updates to the comic and exclusive artworks which aren’t available to non-paying readers.

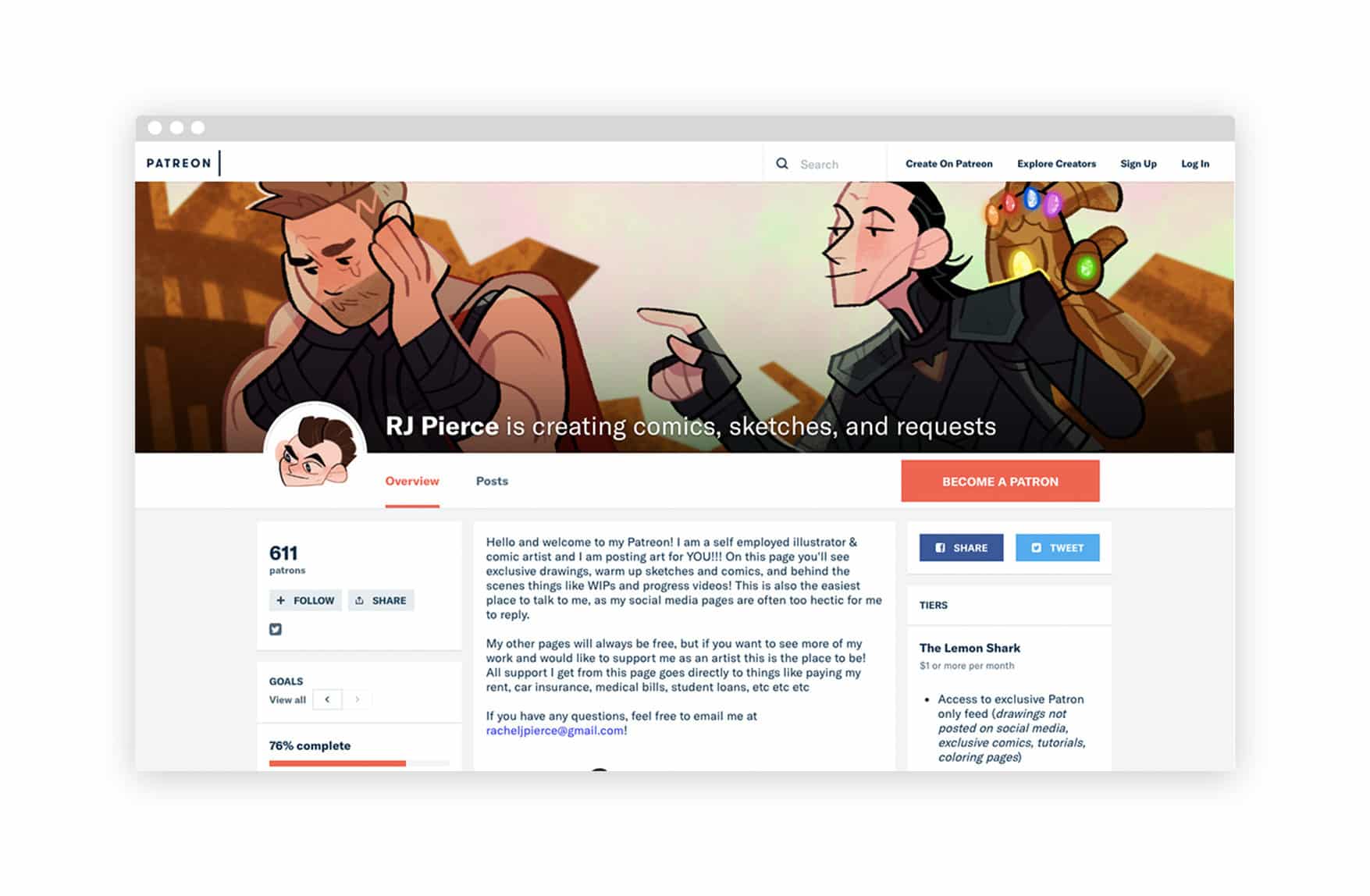

Oseman stressed that, as a self-employed creator, Patreon “makes me feel much more secure in my career;” she compared the reliability of her Patreon income to the sense of security a regular business employee would feel. Rachel J. Pierce, an illustrator and comics artist, described a similar experience with Patreon, telling me, “Patreon has made it possible for me to leave my part-time job and work on freelance art full time.” Pierce, who has been on the platform since 2015, has 612 patrons. “In addition to creating more content for the page, this also allows me to pursue personal projects that I wouldn’t have had time for otherwise,” she adds. Pierce told me that most of her patrons found her through other websites. She promotes her Patreon to more than 150,000 engaged followers on her Instagram, Twitter, and Tumblr. On Instagram, Pierce’s posts routinely receive hundreds of comments from fans who are clearly close followers of her comics. It makes sense that these are people who might be willing to commit a small amount of money each month to help Pierce cover her “rent, car insurance, medical bills, student loans,” as she explains on her Patreon.

Sam Hurd, a self-employed photographer who’s been using Patreon since May 2017, frames patronage less as a means for his fans to help him out, and more as a chance for them to join an exclusive community of photography enthusiasts. Hurd currently has 954 patrons, who receive access not only to behind-the-scenes looks at his photo process, but are also able to join in group photo critiques and pose technical questions to Hurd. “I’ve been full-time self-employed for six years and five of those were spent with irrational fears about where my next paycheck was going to come from,” Hurd told me. “Now that’s not nearly as much of a concern.”

The Washington, DC photographer says that he decided to join Patreon “out of frustration” after the blog posts he was sharing on his personal website kept getting picked up by larger platforms. The bigger sites would sometimes credit him, he says, “but they would link back to me in ways that didn’t help for my SEO, and they’d reap all the monetary benefits from ads and growing their readership.” Seeing that people were interested in what he had to say about photography, Hurd moved over to Patreon. Although Hurd has close to 200,000 followers combined on Facebook and Instagram, he says it’s nevertheless “been a very long and uphill battle converting people to Patreon. A lot of it is just educating people on what Patreon even is.”

Patreon’s Carla Borsoi echoed the sentiment that educating one’s existing followers on Patreon is key to success on the platform. “For up-and-coming creators, what we find is that they can sometimes start a Patreon and it can be really difficult to build a Patreon and build your business at the same time,” she said. “The product itself is really designed to build that membership business.” She added that the company hopes creators understand this before coming to Patreon. While the site offers various guides on how to get set up, Borsoi acknowledges that Patreon works best for those creators who already have an audience, rather than those who are looking to build one.

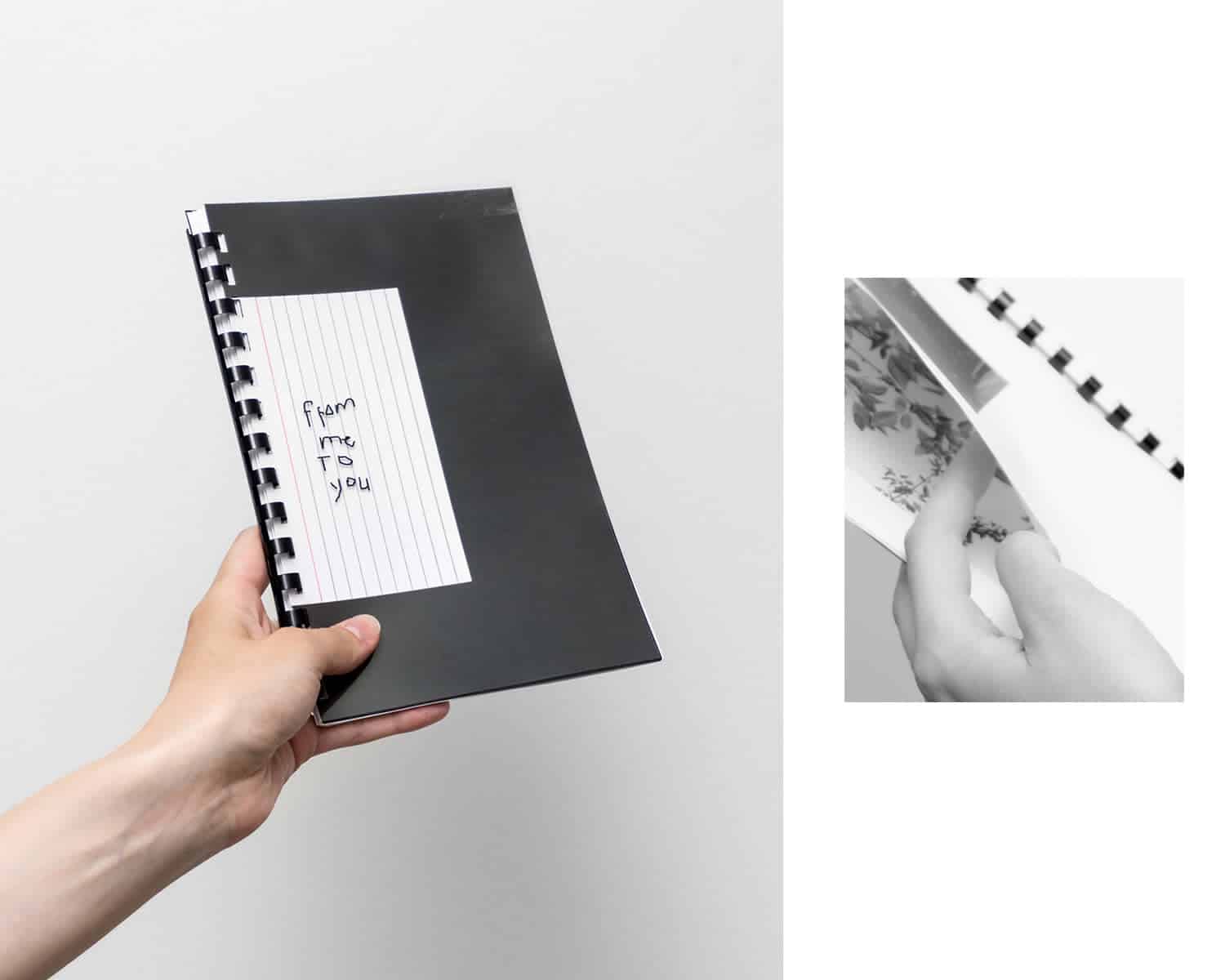

A project from Grayson James’ Patreon

Grayson James is a Toronto-based artist, writer, and recent graduate who started using Patreon in April. So far he has just six patrons. But when I asked if he planned to stick with Patreon in the future, his response was “Hell yes.” Hoping to slowly grow his current modest following, James sees Patreon as a long game. Compared to the gallery world, he says, “it seems like a way, way, way, better economic model for artists to be following.”

“The commercial gallery system is wildly precarious for working artists,” James told me via email. “You have one, maybe two shows a year, and if you don’t sell your super expensive works you have no money. In addition to that, I have zero interest in building a practice that is centered on making luxury items for the wealthy. I would way rather sell 100 books for $15 to my friends and peers than I would one $1500 framed print to a collector, who I can only assume has done nothing to earn their wealth, or my respect.”

James became interested in Patreon through podcasts, he says, and Brad Troemel’s Instagram. The New York-based artist and writer, who has about 65,000 Instagram followers, does a monthly artwork giveaway for his patrons and also offers them in-person studio visits and exclusive access to paywalled content. With 694 patrons, starting at $5 and up, he’s making at minimum $3470 monthly from Patreon.

Troemel’s method of offering physical rewards to patrons resonated with James; his $15 patrons receive monthly publications that he makes by hand. For just $5/month, patrons receive a 18×24″ poster, a print, and a sticker. James also sells work through Successful Press, the small press that he runs; the timeline enforced by Patreon use motivates him to keep producing new work monthly. At rates like these, James’s Patreon seems more about hosting his work and sharing it with others than actually turning a profit. But, he tells me, “The actual upkeep required to run the Patreon is negligible.”

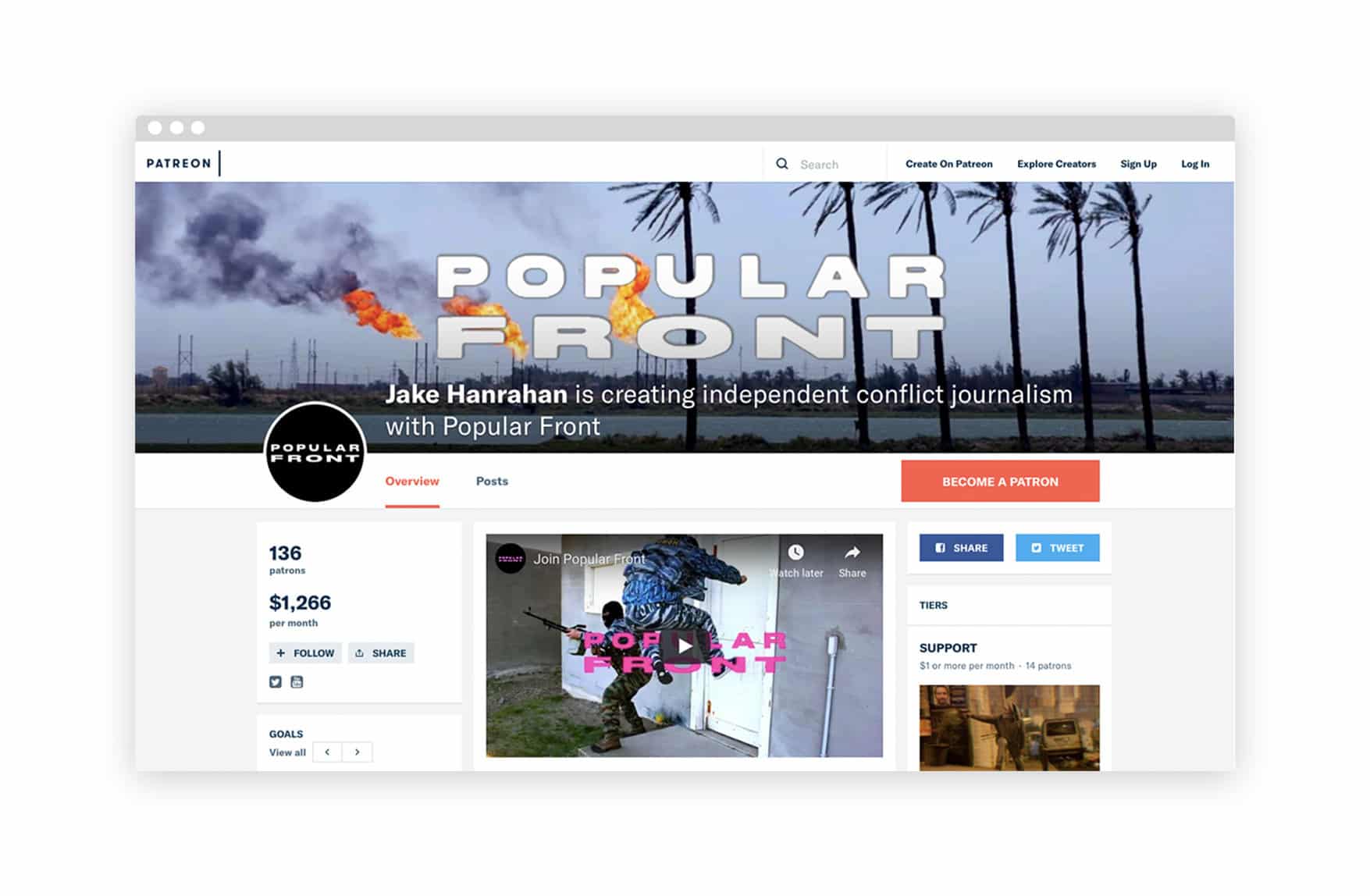

Freelance journalist Jake Hanrahan voiced a similar perspective on Patreon. The British reporter, who focuses on conflict reporting, started using the platform to promote his podcast Popular Front. After starting his career at Vice News, Hanrahan has worked with ProPublica, The Guardian, and the BBC; an established reporter, he turned to Patreon not to raise money to support himself but in the hopes of breaking even on the podcast. A personal side project by Hanrahan, Popular Front aims to cover under-reported and overlooked stories. “I saw that there was a bit of a gap in news reporting and conflict reporting, where the really niche details are not discussed enough,” Hanrahan says. He hopes that Popular Front can offer an uncensored, detailed discussion of important news that might not make it to the front page of major publications. “I don’t think you can fully understand a situation without understanding the small details,” Hanrahan told me. “The world is not made up of easily digestible situations, it is made up of niche, intricate details, which I think need talking about. Nuance is important as well.”

Since its first April episode, which focused on far-right militants in the Syrian civil war, Popular Front has attracted 136 patrons, and is currently making $1,266 a month. Hanrahan hopes to eventually shoot documentaries if Popular Front gets enough support. “I guess if it got to the point where I was making enough money to live off of, Popular Front would become my full-time job,” Hanrahan says.

Popular Front on Patreon

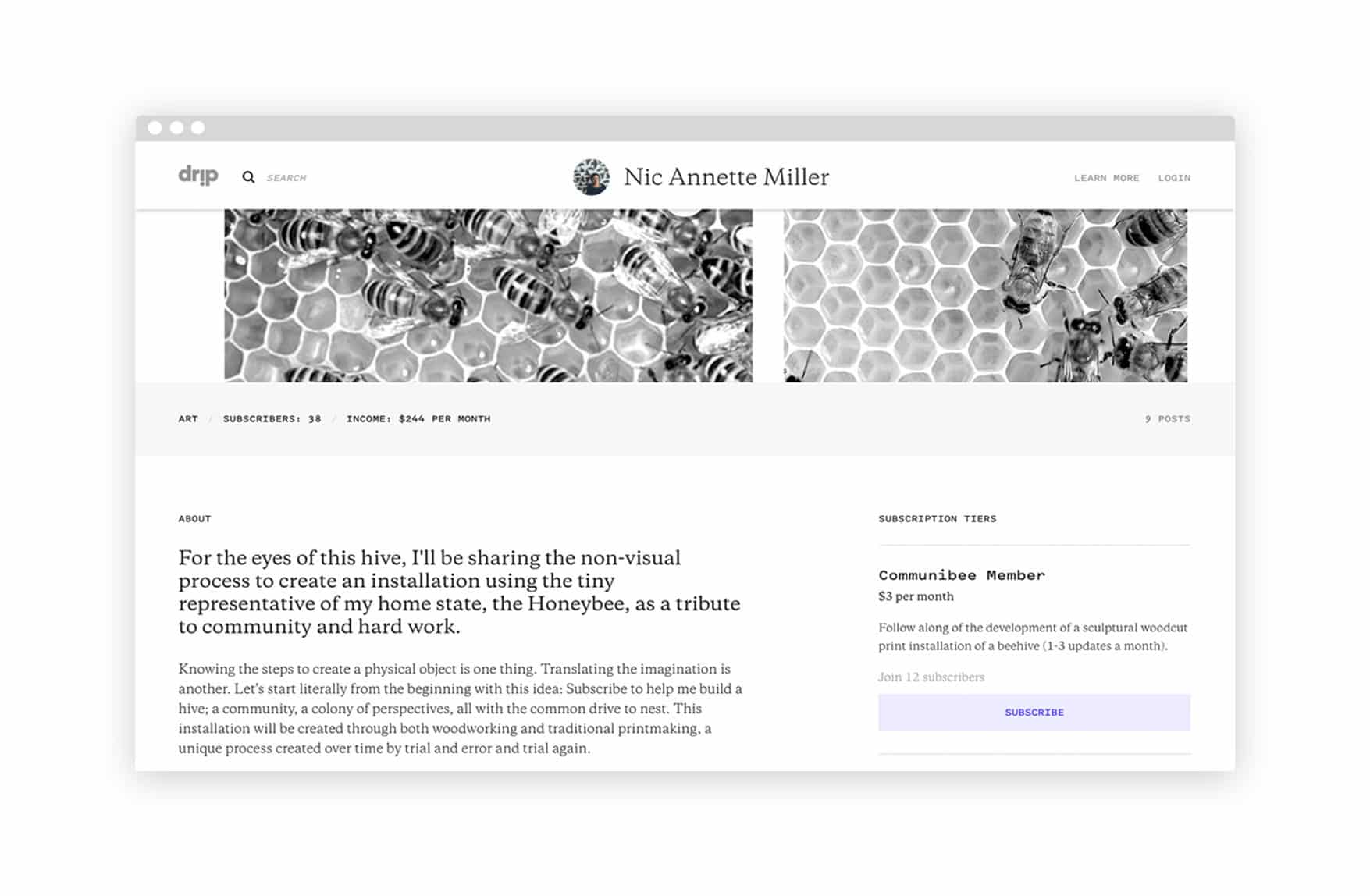

Patreon isn’t the only online subscription-based option available to artists looking to experiment with crowdfunding their work. The recently re-launched Drip, a platform purchased by Kickstarter in 2016, has a similar premise. Originally launched in 2012, Drip initially focused on helping musicians find financial support. “There remain large groups of artists and creators who don’t see subscriptions as fitting their creative practices,” Kickstarter’s Perry Chen wrote in a 2017 blog post about the brand’s relaunch of Drip, which saw the platform marketed to a wider range of creators. “Our goal with the new Drip is to change that.” Drip didn’t respond to a request for comment, but I reached out to Brooklyn-based artist Nic Annette Miller to ask about her experience on the platform.

Miller says she was invited to try Drip when it relaunched in November 2017. She hadn’t heard of Patreon at the time. “Crowd-sourcing hasn’t been a focus of mine, and is honestly out of my comfort zone. But with Drip, I like how the focus is more on supporting an artist in their various multi-level process of developing something from seemingly nothing.” Miller currently has 38 Drip subscribers and makes $244/month from the platform. For $3/month, subscribers are able to follow along with Miller’s creative process as she works on an installation project inspired by beehives. Her model is similar to James’ approach, with subscribers following along for updates on ongoing work as well as special rewards. For $8/month, Miller’s subscribers will receive a limited edition 11×14″ print when her project is complete. “With Drip, I can put the monthly support directly towards what I’m building,” says Miller. “And on a personal level, it’s incredibly encouraging to have people who believe in what I’m making and want to literally see it the whole way through.” She says that she uses her social media channels as well as her newsletter to promote her Drip, adding that “the majority of my subscribers are the ones who have been following my online meanderings for years.”

Clocking in at around 8,200 followers combined on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, Miller’s online following certainly isn’t huge. But with just 38 of those people engaged enough to sign up for her Drip, Miller has been able to generate a not insignificant amount of extra income. She says she would recommend Drip to other artists, noting that her behind-the-scenes approach is just one example of the various ways the platform enables creators to share their work. Like other artists I spoke with, Miller cites a paying audience as a helpful source of motivation, pointing out that sharing your creative process with others can be a useful way to learn from mistakes and grow as an artist. “On one hand it’s incredibly vulnerable to share a lot,” she says. “But on the other, it’s all part of the experience and should be more widely known. Looking back and seeing all these obstacles is really nice to remind myself what it takes to create.”

Nic Annette Miller’s Drip page

A lot of the creators I spoke with, both the well-established and the beginners, stressed the emotional support that Patreon can provide as much—or sometimes more—than the potential financial security it offers. “Even if there are just one or two people out there who are subscribed to your Patreon page, that support can provide a little extra income and help create a sense of loyalty with some of your biggest fans,” Athens, Georgia-based illustrator Katy Lipscomb told me. “Even if the monetary reciprocation is relatively small, just seeing that people genuinely believe in what you’re doing can mean so much.” The recently-graduated art student joined Patreon in 2015. “Patreon really can have an enormous impact on your financial security as a creator,” she says, adding that she used to “heavily rely” on Patreon as part of her monthly salary. Lipscomb took a hiatus from the platform in 2016 to focus on completing her BFA at the University of Georgia. She says she uses social media to find patrons; she has an audience of close to 300,000 fans on Instagram and Facebook, and 61 patrons. Lipscomb acknowledged that building a social following is often an important element of a successful Patreon. “Patreon can be an incredible platform for creators, but it is entirely what you make of it.”

While it’s clear that some artists find a lot of value in Patreon, especially as a source of community and peer support, some creators express frustration with the platform. Writer and photographer Brent Knepper recently shared his experience with Patreon in an article on The Outline, writing that, “When I first signed up, I thought I was the perfect match for Patreon’s model. But now I’m realizing that as a struggling photographer without a massive social media following, I’m probably not Patreon’s Target Creator.” Knepper argues that the vast majority of Patreon creators are making only a negligible amount. Since setting up a Patreon account doesn’t cost anything, you could also argue that creators have nothing to lose from trying it out. On the other hand, setting up an account does take time, and when you’re a freelancer, time is money that you can’t always afford to spare.

Ultimately, what I learned from speaking with these creators is that Patreon is a highly useful tool for some people and a big letdown for others, and those two groups of people aren’t always who you’d expect. Some artists with very small followings on the platform are satisfied with the moral support, sense of structure in their practice, and modest amount of cash that Patreon facilitates. Others who look to the site as a moneymaker may come away feeling annoyed when patronage doesn’t result in enough money to make the upkeep of Patreon worthwhile.

Rachel J. Pierce’s Patreon page

While some successful users, like Alice Oseman and Rachel J. Pierce, are making what could be a living wage through Patreon, it does seem likely that they are in the minority, as Knepper suggests. Then again, just because someone has only a few patrons doesn’t necessarily mean they aren’t making any money. “It’s really hard to talk about what’s the optimal number of patrons to have, because it’s so dependent on the creator and what they’re offering as their membership tiers and benefits,” Carla Borsoi told me. “For example, you might see someone that only has 20 patrons on the platform and you won’t see how much they’re making… But they might have 20 patrons who are all contributing 50 dollars or 100 dollars each month. That membership can be a very strong financial signal to the creator. Whereas you might have someone who is more support-based as a creator, and they might have 500 patrons who are only giving them one to three dollars.”

When I asked Grayson James if he’d tried any other similar crowdfunding methods of financing his work, he said he hadn’t, but he also pointed out that his Patreon is “an archaic model,” in that “it’s more or less a newspaper subscription.” The idea of patronage is also, of course, an archaic one. It used to be that the king, or the government, or some duke, would pay for artists to live and work, and talented painters wouldn’t have to also hold down jobs as baristas.

Today, it’s becoming common for corporations to support artists in this way—Red Bull and Adobe both have well-established creative residency programs, for example. Artist residencies, corporate or otherwise, typically offer the opportunity to create work in a new setting while your expenses are paid for; while they can be exciting chances to broaden your practice with a change of scenery, residencies obviously aren’t long-term options for artists looking to sustain themselves. For so many artists, a day job is a must if they want to pay the rent and have money left over for groceries, let alone the often expensive art supplies and studio space needed to create their work.

It makes sense that even artists without large online followings would look to Patreon for a chance to earn a little extra money—and it seems that, for some, the platform does help deliver at least a small boost of financial support, like an ongoing online-based residency that comes live a live audience. “It’s such an easy and pleasant way to work through my ideas and make some extra money that it seems crazy to me that more people aren’t using it,” Grayson James told me. Then again, a lot of people may be hesitant to crowdfund an income via Patreon because it feels weird to ask for payment without offering concrete work in return. Jake Hanrahan, for one, voiced this concern. “I thought about making a Patreon like, ‘Hey, support my work, blah blah blah.’ But it doesn’t feel right. I want to create something first, and then if people like it they can support it. Not the other way round.”

However, talking to successful Patreon users showed me that these aren’t people who ask for support without giving back, but instead actively do a lot of work for their patrons (sharing works in progress, studio photos, professional advice, and so on). And a lot of this work is labor that many artists not on Patreon are actually already doing, for free, on social media. Especially for emerging artists, maintaining an active and curated social media presence is often an unavoidable aspect of a creative career. It might feel weird, but if you’re already doing this work for free, why not at least try to get paid for it?

More on the business of creative work:

How My Day Job Inspires My Creative Work

The Link Between Creatives and Underemployment

The Challenges of Overcoming Creative Imposter Syndrome