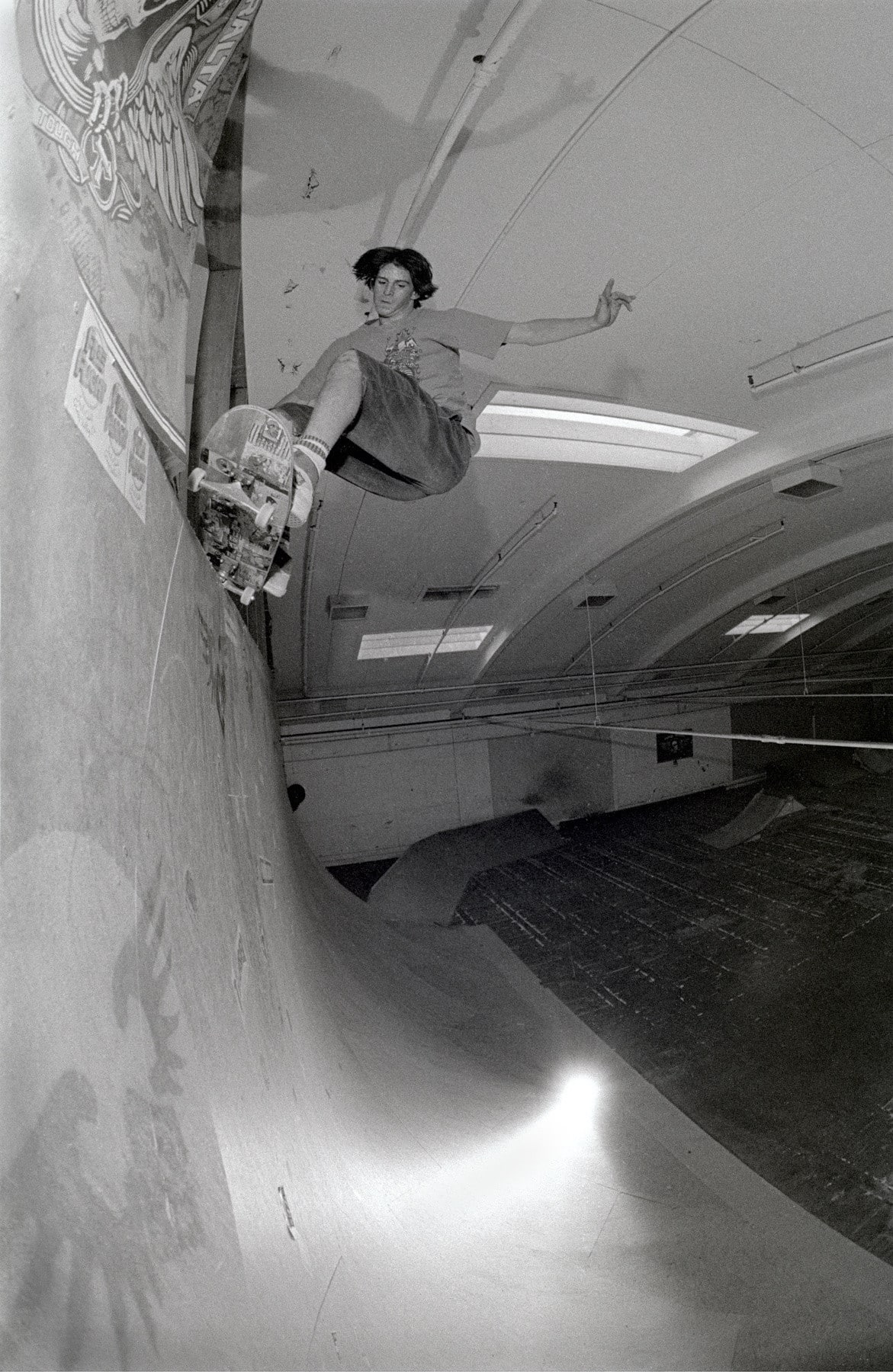

Back in the mid-’80s, when skateboarding was not yet the huge phenomenon it was soon to become, Tobin Yelland picked up a camera his mom had lying around the house and started photographing his friends. There wasn’t much competition for skate photographers at that time, and Yelland managed to get a couple photos published at 15 years old. This net him a wild $100 and the prospect of a future doing something he loved.

“It was like, ‘Wow, God, wait, $100. This could be a job,’” Yelland says over the phone from the kitchen of his friend’s art studio in Los Angeles. “From that point on, I wanted to be a photographer. I thought that would be an amazing way to make a living.”

Like a lot of photographers, Yelland was mesmerized by what a camera could do—the idea that, at least until educating yourself, making a physical memory of something seems almost like wizardry. Along with his enthusiasm for the scientific challenge of figuring out how exactly to make a perfect exposure or print, it’s a feeling that’s still stuck with him now, decades later.

“I think my original urge was just looking at a camera and trying to figure it out. Like, ‘What does this do?’ It was magic, being in the darkroom developing a print from a white piece of paper to an image, waiting for that image appear. It’s a cliché story, but it still feels like magic.”

It still feels like magic.

From there, becoming a professional photographer wasn’t too crazy of an idea—a room in an apartment, at that time, in San Francisco cost about $300, and Yelland figured he could get more work published five or so times, which would cover his monthly expenses. He decided not to go to college and put all of his energy into skating and skate photography. Before it supported him completely, he did the same thing most artists do, which is find jobs that pay the bills. He was an electrician’s assistant, took construction gigs, delivered vegetables for restaurants—anything that could keep him afloat, jobs he could dip in and out of as he needed.

“I photographed every day,” Yelland said. “That’s what I did. It was ‘make or break’, because I didn’t want to go back to construction. It was like, ‘I’m just gonna do this 24/7 and be a photographer.’ My mom was an artist, so sometimes I photographed her doing her art, or got hired for different art jobs. Bands would ask me to photograph them and pay me a little bit, or I’d get photographs published in different publications around San Francisco. Then I got opportunities to do still photographs on films and movie posters, some fashion stuff, some advertising. One thing leads to another. You meet a group of people on one project and then stay in contact with them, and can bounce back and forth and do more work with more people. It just gets bigger and bigger.”

I photographed every day. It was ‘make or break,’ because I didn’t want to go back to construction.

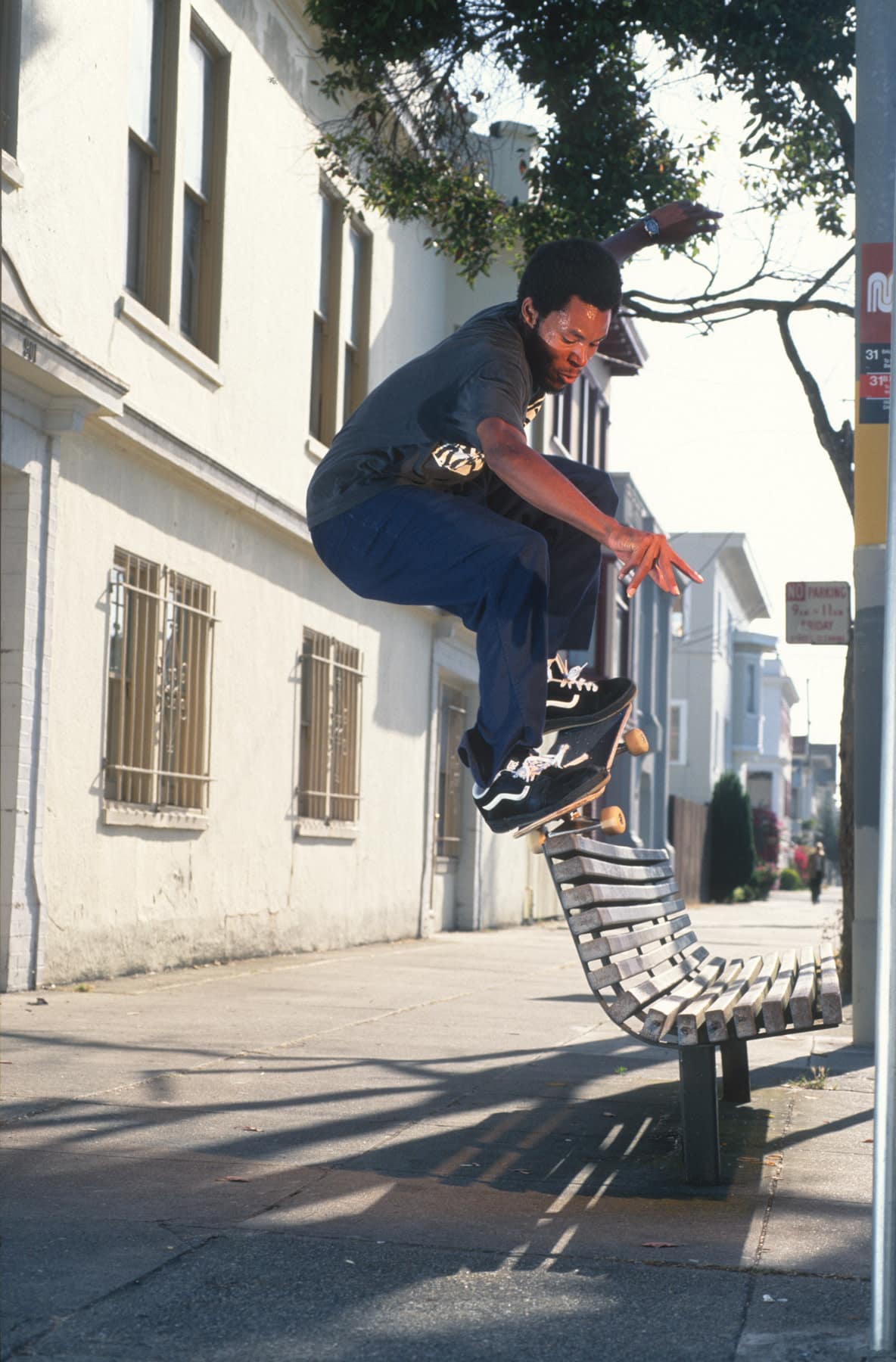

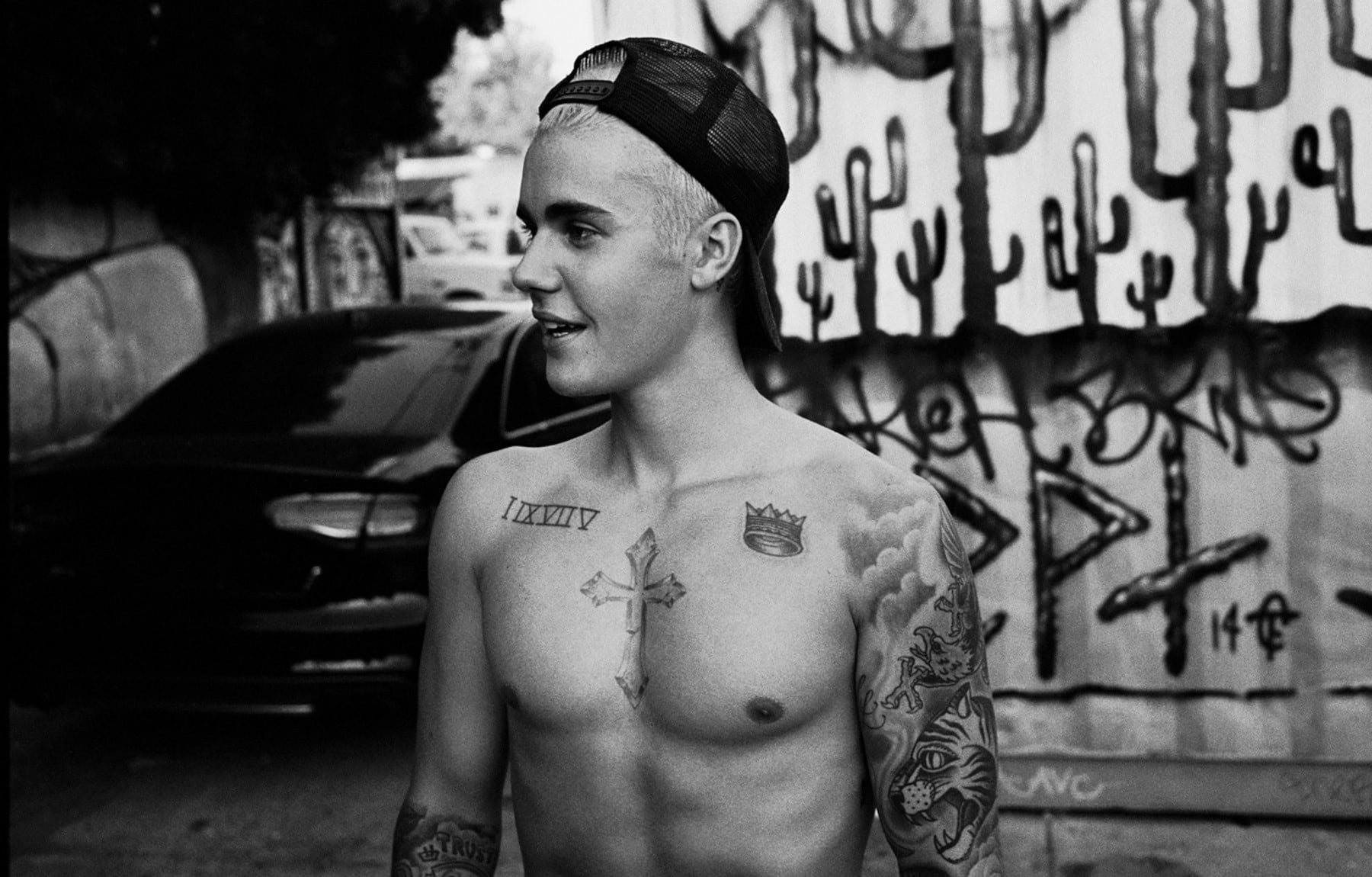

Since starting out with just a borrowed camera and a few pals skating around town, Yelland has shot celebrities like Justin Bieber, Henry Rollins, and Jason Lee. He’s worked for everyone from * The New York Times* to Hypebeast, as well as campaigns for brands like Fender, Calvin Klein, and Vans. In addition to shooting stills and movie posters, he’s been exhibiting his photography and film work for over two decades at spots like the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Philadelphia’s Institute for Contemporary Art, and Dazed and Confused’s Gallery in London. It’s one thing to pursue a passion and build a portfolio, but quite another to turn that into making a living. And Yelland considers that a two-part process.

“You need to build a body of work, and then also build a network of people, friends, and like-minded people,” Yelland says. “It takes digging, like, ‘Alright, it’s June 15, and I have bills due on July 1.’ So you just begin to make phone calls, emails, get out there, go to parties, meet new people. I think that’s a big part of it—meeting new people, just being outgoing. The more I’m confident in what I do, the more I like what I do, the more people I can share what I do with, the more opportunities come to me.”

I feel like I’ve stolen something, or like I just put money in my pocket, when I get a good photograph.

It helps when you’ve got an aesthetic as natural as Yelland’s. In his portraiture and lifestyle work, his subjects always look infinitely comfortable, and his photographs of skateboarding feel timeless, like they were taken by someone who was just around at the right time in the right place, without any unnecessary production or pizazz. The latter is partly thanks to the fact that the dude is a bona fide product of those scenes, but also because of where he was finding inspiration. Photographers like Craig Stecyk, who shot the Dogtown and Z-Boys guys, and Mörizen Föche, aka Mofo, are both big influences. Both have an aggressive style, and sought out interesting, high-energy characters, no flash. Yelland looks to create similar intensity in his portraiture, which makes his subjects feel multidimensional.

“I do feel like I’m trying to steal a moment, like I’m trying to get away with something in my photography. I don’t wanna belittle anyone with the photograph I’m taking of them, but I do feel like I’ve just stolen something, or like I just put money in my pocket, when I get a good photograph. I’m like, ‘Wow! I scored!’ And I scored for myself. There’s that search for that good feeling when you got a great photograph. That’s definitely what I’m searching for.”

For young photographers looking to find their own natural style, Yelland has some impossibly simple but very effective advice. The first part isn’t too far off from fellow photographer Ryan McGinley’s counsel during his 2014 Parsons commencement speech, in which he urged students, “Don’t compete.”

“Try to occupy the majority of your time photographing what you want to photograph because you want to photograph it,” Yelland says. “Not because it seems like the right thing to do. Also try to learn from people. Search out mentors. I think the most successful people, or the people getting the most inspiration, are the people who aren’t afraid to knock on someone’s door, make a phone call, or send someone an email saying, ‘Hey, I love your work, do you mind if I take you to lunch or buy you coffee and ask you some questions?’ Learning from people, learn how other people photograph and navigate the job of being a photographer, and find a way to make a living at it but also be creatively fulfilled with it. It’s kind of a riddle.”

A lot of creative people and scenes have been born out of skateboarding, which seems to attract outside-the-box thinkers, like Ed Templeton or Mark Gonzales. It could be the sport’s marriage of physicality and art—when you watch The Gonz skate to John Coltrane’s “Traneing In”, it’s so alien to the average perception of what skateboarding is. It’s fluid and natural and fun, and seems less like a feat than just a guy who found an easy way to get around. Plus, like any creative pursuit, the only way to persevere is to get used to failing over and over again, never sure whether a result is even going to arise out of your attempts at a trick or an idea. Skateboarders are used to getting knocked down and getting back up again. That’s an inherent advantage as an artist. And something Tobin Yelland is used to.

“You have to fail most of the time,” Yelland says. “Some people can land every trick, or most tricks. But the majority of the people I see skateboarding are trying it, falling, and seriously hurting themselves again and again, and then making it once. And then maybe their friends took a picture or a video of them, or maybe not. But you do it once and you’re like, ‘Wow! I did it.’ That’s the reward. It’s okay to fail, and failure is part of it. If you’re not failing, you’re not really trying.”

See more of Tobin Yelland’s photography at his portfolio, built using Format.