In the first piece, A Practical Guide on Breaking into Public Art, we reviewed the steps from proposal submission to project realization. In this second half, let’s explore the fun stuff: the artistic and conceptual challenges specific to making public art.

Artistic & Critical Issues To Consider

As an artist, ask yourself what is the purpose or the drive to make work for the public and how does my work change as it enters a new context?

It’s also important to ask broader questions like: why do public spaces need art and how will my art object benefit the community by its placement in public? As we ask ourselves the fundamental questions, we should also consider the significant process of translation that happens when we transform our “regular” studio output into artworks meant to live in the public realm, connecting to and interacting with community members. We will cover the tangible factors that we must consider including: scale and proportion, site specificity, durable materials, as well as the emotional; finally letting go of our work as it becomes something new.

Scale

This is probably the biggest hurdle to overcome as you produce artwork for public spaces. As you prepare objects for a specific space and a public audience scale presents aesthetic and conceptual challenges across many disciplines including sculpture, photography, painting and even digital art.

Scaling up may seem deceptively simple. However, it isn’t as easy as simple sizing up your maquette, collage or table-top sculpture to fit the larger dimensions. For any work, there are physical considerations of space that need to be considered; are there sight lines, ceilings, wall heights or staircases that interfere with the viewing of every aspect of the artwork? If the artwork is in a public hallway or staircase that is very narrow, your viewer won’t be able to step far back to view the artwork as a whole, so you need to incorporate smaller vignettes within the longer composition to make coherent or visual sense. Since only 3 – 4 feet is viewable at a time in a tight public corridor, the artist needs to consider how close the view will be.

The Birds, Myfanwy MacLeod, 2010, Stainless steel, hardcoated EPS foam, bronze, Milton Wong Plaza at Olympic Village, Vancouver, BC

For sculptural artworks, the usual culprit is proportion; considerations for the context and harmony of the artwork in relation to its surroundings. Work can either seem too big for the space, making the viewers feel overwhelmed or diminutive; or alternatively, too small for the space where the piece gets lost or has no impact.

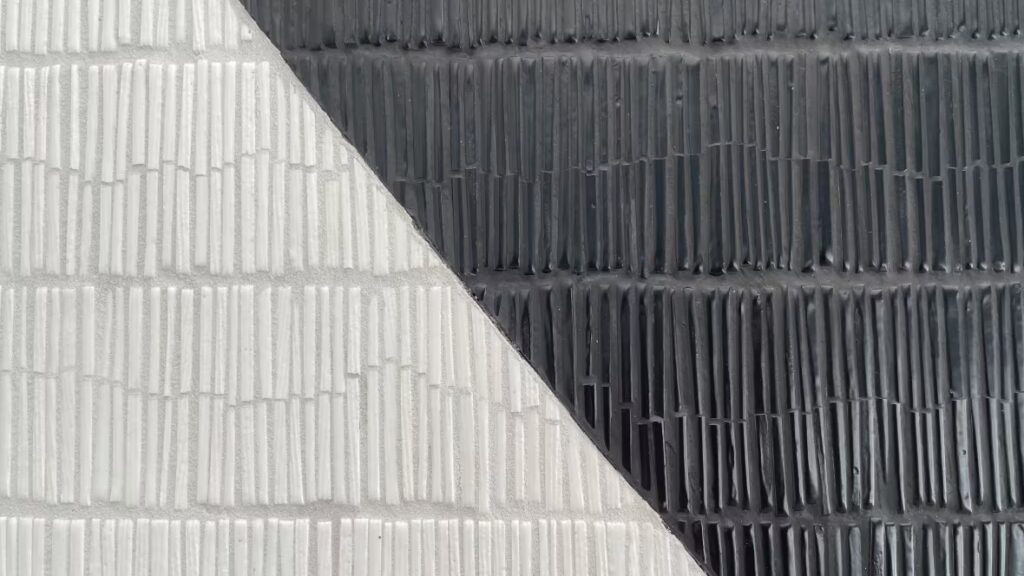

When considered from maximalist and minimalist perspectives, scale can instead work to your advantage. For example, in Myfanwy Macleod’s sculpture “The Birds”, the artist brings the tiny and ubiquitous sparrow into monumental scale. Perched on a city bench, the work’s integration with the infrastructure is perfectly congruous, and the birds themselves feel both intimate and enormous. Alternatively, in Micah Lexier’s Two Circles, the artist plays with the tension of proportion moving slowly from overwhelming to intimate; with two seemingly simple open and closed circles dominating the white walls of an expansive lobby. On closer inspection, the viewer sees the wall is built of intricately handmade, and snapped, ceramic tiles which create a staggering rhythm. For Lexier, it is the small detail, the piece of the whole, that feels sublime while the larger expansive views convey something “simpler.” The poetry and elegance comes from the confluence of extremes; intimacy and grandeur, what is tactile and what is visual, harmony and the sense of splintering. Some public artworks can fundamentally misunderstand the minimalist gesture and transformational possibility of scale. Sometimes the right sound, when made louder, becomes intolerable.

Micah Lexier, Two Circles, 2016, two walls – 30 x 26 feet and 47 x 24 feet, hand-glazed and hand-cut sticks of ceramic tile, Bay Adelaide Centre East Tower, Toronto ON, images copyright CBC

Site-Specificity

I think a central tenet of making public art is a need to engage with the specific context of the site; the surrounding buildings, architectural styles, overall neighbourhood presence, the history of the place and its people.

While not always a main criteria for public art in Requests for Proposals (RFP’s) or design prompts, site specificity is crucial in activating the public space in a positive and meaningful way.

There have been recent trends of empty and dull geometric shapes masquerading as thought provoking modernist sculptures; think imitations of Mark Desuvero, Alexander Calder or Henry Moore dropped down onto an empty plaza or in front of a new condo development. This zombie formalism has seemingly little to do with the surrounding architecture or space. UK sculptor Rachel Whiteread describes this as ‘plop art’, a phenomenon in which the object “doesn’t really bear any relationship to anything else. […] Art has gotten extremely popular which is great for many reasons but I think a lot of public sculpture is ill-thought-out and put in places it shouldn’t necessarily be. It then becomes something that is sort of invisible. People don’t even notice it. I think art is there for a reason and should be respected and looked at […].”

To avoid this risk, be mindful of the kinds of spaces your work will be inhabiting and how people will interact with it. Common public art placement to consider:

- transit corridors

- outside of academic institutions or libraries

- at the center of a public plaza alongside trees, benches and a fountain

- across pedestrian bridges or traffic islands

Each location presents different challenges to planning, materials and logistics, as well as the other factors. In making art for the public, the audience of a place or community should be top of mind.

Underground

A surprising and charming masterclass in site-specificity and transforming the mundane, Bill Brand’s Masstransiscope turns the Manhattan-bound B or Q subway cars departing from DeKalb Avenue Station into a movie machine. A monotonous experience becomes magical as a colorful, animated zoetrope immerses commuters as the train moves through the tunnel. Here the audience is one that may be typically engaged with their devices, books, and naps, suddenly activated by this film playing around them. With a captive, but bored audience, there is great chance you can give them something unexpected and delight them

Outdoors

Her Long Black Hair by Janet Cardiff guides participants through an immersive audio visual experience with the artist. Meandering for a 46 minute walk through NYC’s Central Park, Cardiff, present in sound and image, encourages reflection on the relationship between nature, architecture, time, sound, and physicality. Interweaving stream-of-consciousness observations and blurring fictional events with true local history, the narrator prompts you to view the archival photographs and see the park’s history in contrast to their experience of it in the present, using the framework of the past to encourage enjoyment of the park in new ways.

Those who enjoy walking and nature– already a calm, contemplative crowd, are perfectly suited to this artwork which takes time and a willingness to look around them.

In the City

Subverting advertising spaces can be a powerful artistic gesture as you consider the ways in which images exist amongst the visual noise of a city. It makes evident how much of the daily experience of our surroundings is rife with marketing primed to sell us a product or an idea. When planning a public art exhibition using spaces designated for advertisement such as billboards, panels, and LED screens, consider how replacing marketing with an artwork changes both the meaning of the space and the artwork, adding a layer of complexity to each. The space changes how viewers interact with the image, especially in context of the surrounding buildings, structures and streetscape. When very private scenes of family or daily life are elevated and shown in public, there is often a cognitive dissonance between public and private, you may feel as if you are peering into something that should not be allowed to see, maybe something too intimate to be seen on the street.

You can use this site specificity to your advantage as you engage a city square, a glass luxury condo, or a brick commercial warehouse in direct conversation or conflict with your artwork.

In a city where people are moving quickly and look briefly, this is a space you can slow passersby down with a compelling hook, or simply understand the scope will be narrowed to those who still look, read, and see their surroundings.

Jessica Thalmann, cut between the supports and collapse (Hands), 2022. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy of the artist and Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival.

Materials

You will likely have to translate your ideas into and onto more durable, sculptural materials. The traditional mediums used for public sculpture or monuments include cast bronze, stone, ceramic tile, glass, concrete, and various types of stainless or corten steel that are weather resistant and easily maintained. If you are making a two dimensional work like a mural, painting, photograph or any printed material, it’s important to select the right paints, sealants and UV coatings that will maximize the lifetime of your surface, pigments and colours. Be sure to test new brands who may be innovating for longevity and keep your maquettes, molds and copies of the health and safety worksheets for each product you are using in your art object. To that point, to work out any kinks and troubleshoot production errors along the way, make lots of tests with these new materials, first at smaller scales and eventually at the final scale, ensuring no surprises at that stage.

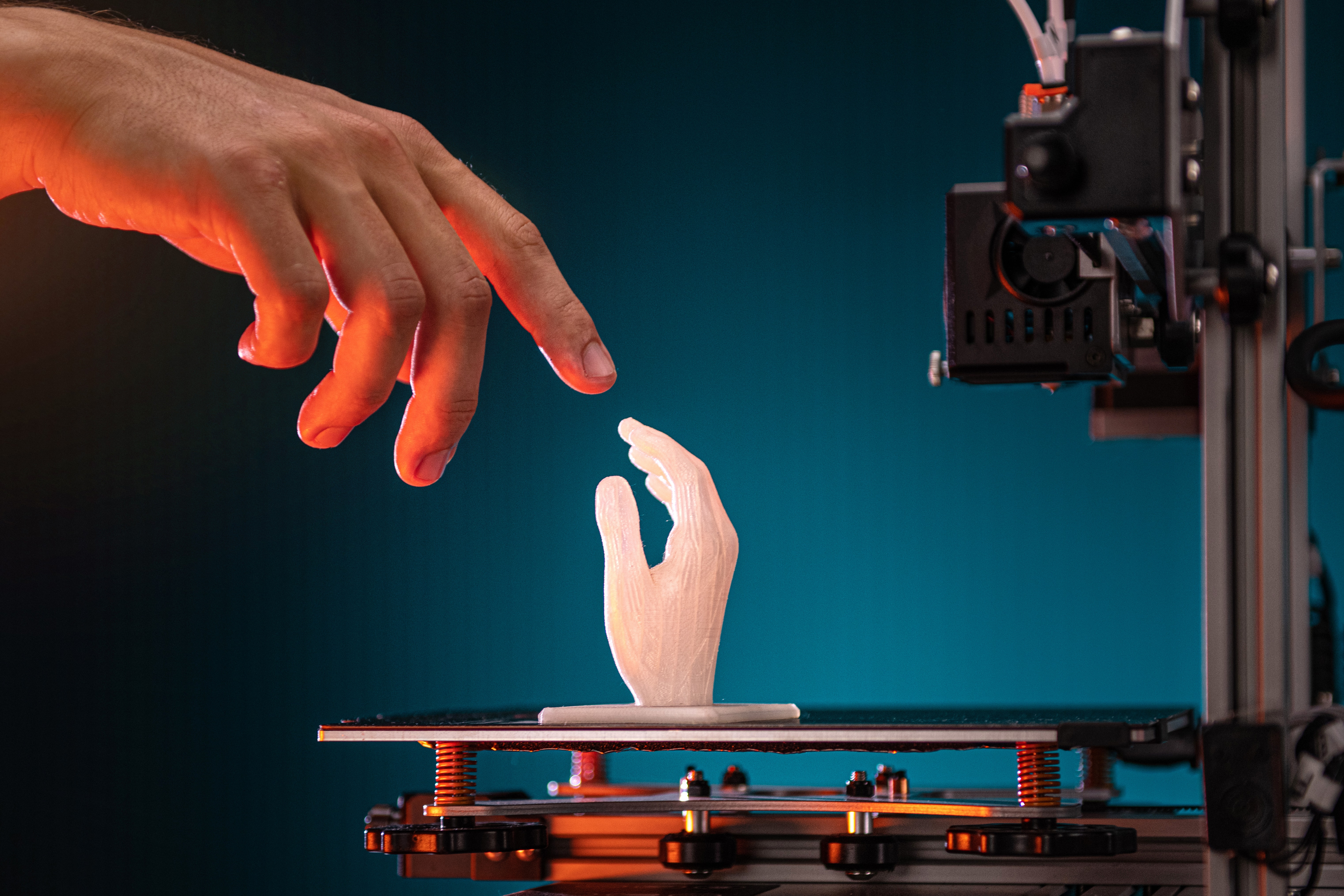

Part of this process is to collaborate with other fabricators, welders, engineers, studios and suppliers that specialize in these durable materials or techniques. This can include, waterjet cutting, welding, large scale metal work, lighting design, 3D printing, laser cutting, direct to substrate printing, graphic design and mounting services. I highly suggest you research several methods by which you can achieve your desired outcome , and from there, studios and fabricators. Choose a collaborative partner with whom you can have a positive working relationship. You will be working with these fabricators, artisans and technicians for a long time and with some highly stressful situations, great communication and trust will go a long way to keeping you both on the same page. Something to factor in is sustainability, and how your efforts to make something new can incorporate used media, surfaces or objects. Recycled materials including rubber have recently been successfully integrated into artworks and parks, an example of this can be seen in Daniel Borins & Jennifer Marman’s Water Guardians sculpture in Toronto. The recycled rubber waterways are integrated with green mounds and provide a bouncy surface on which children can play and interact with the water elements.

Letting Go

This is probably the most difficult lesson to learn: once the artwork is in the public realm, it doesn’t belong to the artist anymore.

For better or for worse, the artwork takes on a life of its own. Community members interact with the piece and new connections are made between viewer and work, work and place, taking on profound meaning as visitors bring their own experiences to the art and site. Others will find the artwork inevitably met with criticism, and in some cases, vandalism.

There are some hard-won lessons learned by established artists in how public opinion can shape and transform the meaning and durability of public art, and these are all factors to consider in conceiving and realizing your project. Your audience, if well considered, and connected to the work, can come to be guardians of the art.

From the examples above, it’s clear that public art can present artistic and conceptual challenges for artists at any stage of their careers. I encourage you to wrestle with the logistical and aesthetic problems that accompany its creation because as many as there are issues, there are opportunities.

You will have fun (and be stressed), I promise.