Sometimes, when speaking with artists and creatives—musicians, photographers, graphic designers, you name it—there’s a palpable lack of excitement when it comes to speaking about their creative process. It’s totally forgivable: not every part of the process is exhilarating, and, having talked about it one too many times, they might feel they’re beating a dead horse. But Jason Lee is nothing if not excited about photography.

When I off-handedly ask about how he got started with peel-apart instant film, Lee unravels everything you’d need to know over a solid 10 minutes, including what type of camera to buy and why, battery conversions, which films to use and where to find them, the different qualities of each, and why he loves every one of them.

The way he speaks is indicative of someone with an unquenchable drive to create, but that would’ve been clear from simply looking at his multiple careers. Lee first made his name as a skateboarder in the early 1990’s, and traces the big awakening of his creative urges back to hanging out with the original “weirdo skaters” and launching his own Stereo Skateboards, where they made videos with Super 8 film, scored skate parts with jazz, and incorporated still work from photographers like Tobin Yelland, Gabe Morford, and Ari Marcopoulos into their videos. But maybe most influential was the legendary skater Mark Gonzales, who Lee deems the “Bob Dylan of skateboarding.”

“He was the first dude to skate to jazz,” Lee says over the phone from his home in Denton, Texas. “That was the cool thing about Mark. Video Days was his idea. It was the first video of its kind—it was just fun. It was full of character, and had an interesting array of musical genres, and it had life and creativity to it. I think that’s why to this day, it’s a lot of people’s favourite skate video, at least of the early classics. That’s what we were exposed to, so I feel blessed skateboarding was able to expose me to so many different facets of creative life, and all the different genres and mediums.”

Lee says being in that environment of skaters, artists, photographers, musicians that “it gets into you and everything you take on after that, it feels almost appropriate. It felt totally organic to get into something like photography.”

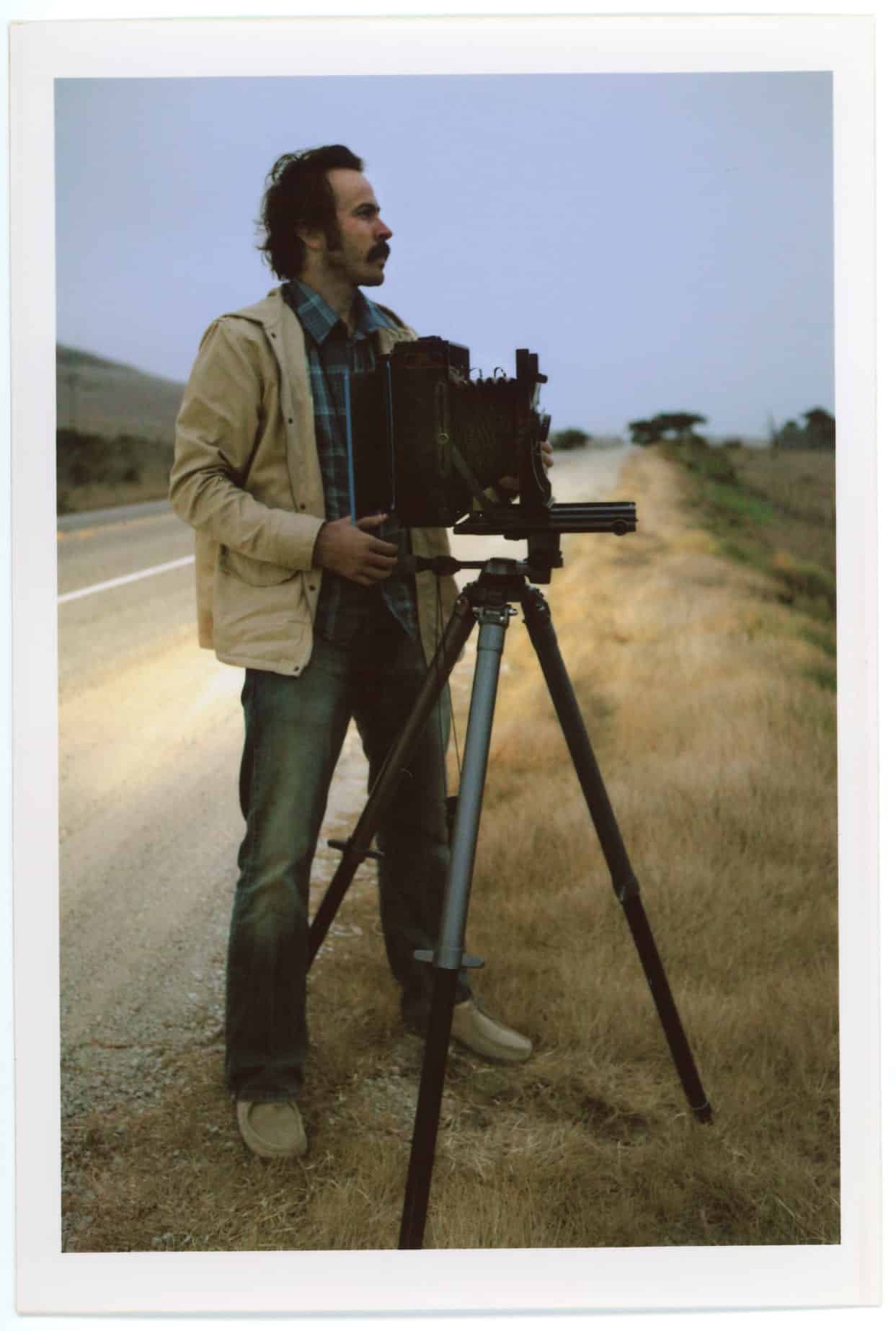

In those days, photography was mostly an interest rather than a career path. Lee is perhaps best known for his work as an actor—you might remember him as the titular character from My Name Is Earl (2005-2009), but if you haven’t seen Mallrats (1995), make it a priority—and it wasn’t until 2001, that Lee picked up a couple professional film cameras, a Leica M6 and Mamiya medium format camera, and started shooting regularly. It quickly became a passion, and that’s where his new book, the first of two volumes with Refueled Magazine, comes in.

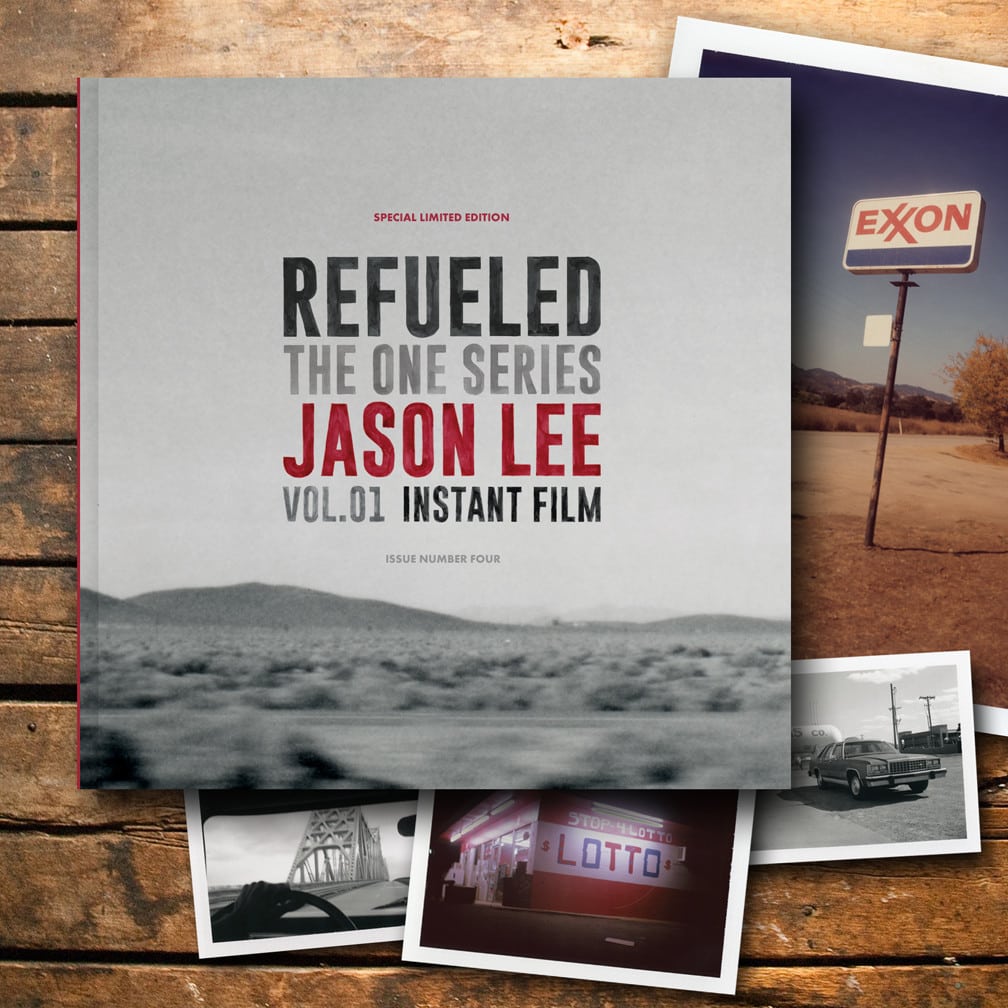

As part of the magazine’s One Series, Lee’s first volume, limited to 500 signed and numbered copies, collects 184 pages of Polaroid and Fujifilm instant photos from 2006-2016. The second, Lee says, will come out next year, and will be filled with conventional film photos from the past 15 years.

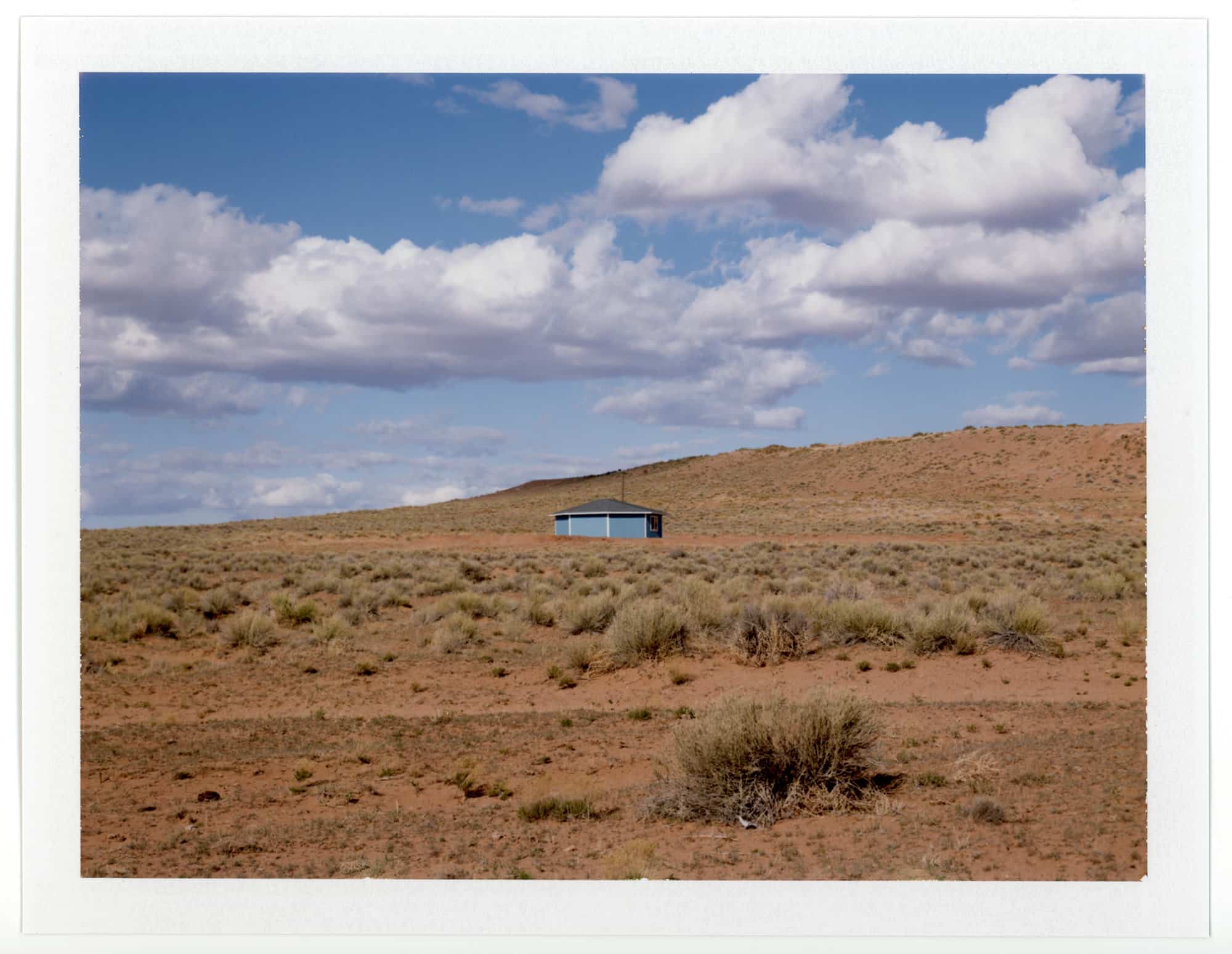

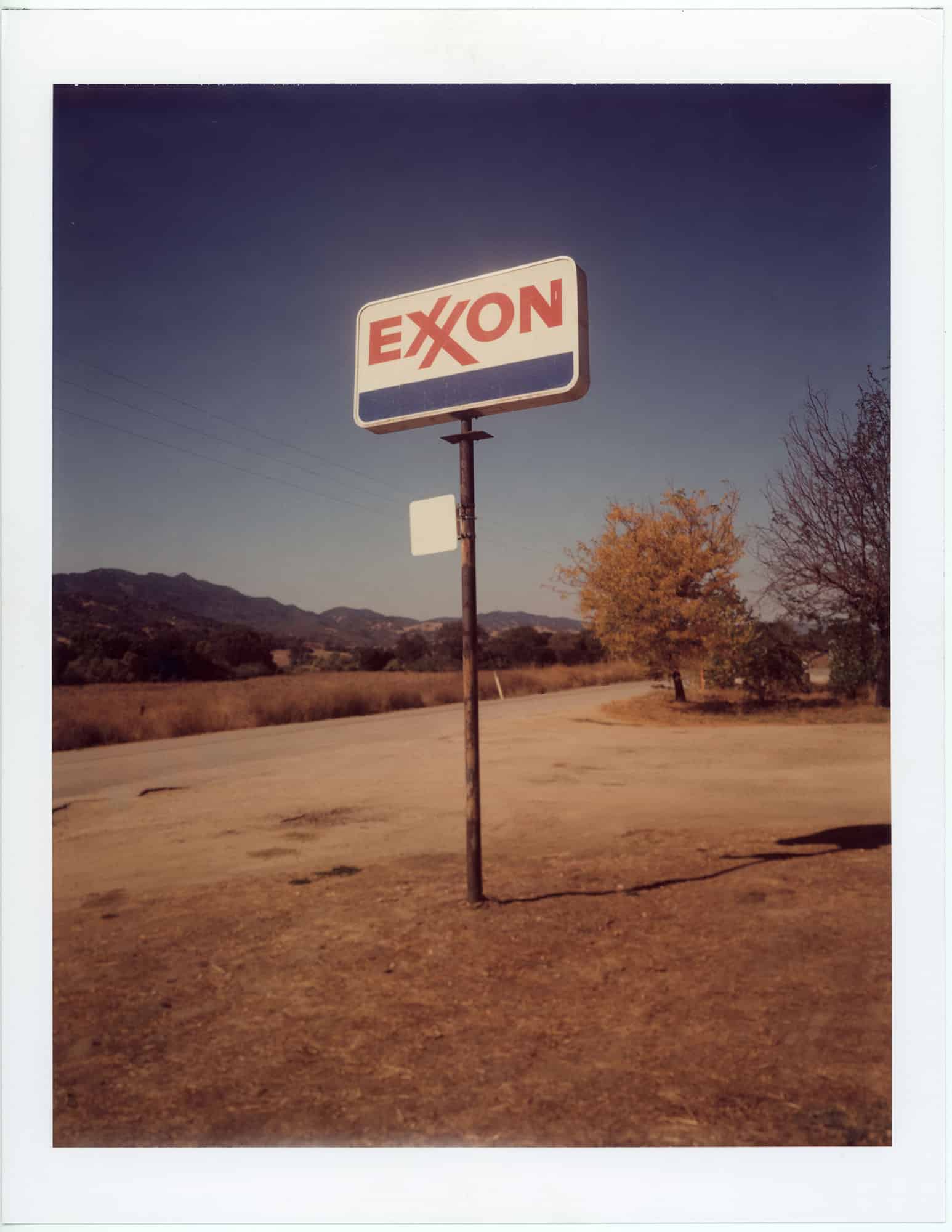

A look at Lee’s Instagram gives you a clear idea of what the book contains: visions of a dust-covered America, forgotten and abandoned gas stations and motels, barren landscapes, and the occasional detached but striking portrait. There’s an unnerving chill that runs through Lee’s work—not sad, but certainly calm and pensive—that conjures up the same feelings you get watching the windswept southern scenes of Paris, Texas.

“Certainly, my aim isn’t to make it depressing, but there is a little bit of a loneliness to it,” Lee says. “In a way, that’s kind of interesting, because it makes you want to stop and maybe pay a little more attention. It’s isolated, in a way. There’s something isolated about it, so you’re focused on what the thing is as its own piece, but then hopefully there’s a cohesive overall piece.”

Lee speaks passionately about arriving at that aesthetic. In his downtown L.A. studio, in the early 2000’s, he was doing a lot of experimental stuff: “strobe lighting and shooting portraits and pushing and pulling film, using different filters.” Then he had a “holy shit” moment when he discovered he could get 8×10 Polaroid film, which he used to buy for $200 at Samy’s on Fairfax. (Now, expired boxes of 8×10 Polaroid film goes for a slightly more steep $1,000 on eBay.) The connection was sparked when he took the Polaroids into the desert.

“I shot some 8×10 and 4×5 Polaroids out on the road, of old churches and gas stations, and there was just something about the film that made it seem even more distant, and desolate, and quiet and removed, and isolated. There’s something about the peel-apart film that creates that kind of feel.”

While instant film can be hard to come by these days (unless it’s by the Impossible Project), and even harder to afford, Lee is adamant there are no disadvantages to the medium, besides the fact most of it is expired.

“As long as you keep them out of sunlight, they’ll never fade. The Polaroid black and white stuff is my favourite film, and I’ve shot a ton of other conventional films. There’s just something smooth and very charcoal-like about it. I like the one-off factor. No two are ever gonna be alike. You peel it, it’s a print, and it’s right there, and that’s it. You scan it, you can make digital Epson prints, but there’s only one of it and that’s it. What you get is what you get.”

Shortly after getting into the large format Polaroid film, Lee saw a Henry Wessel exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and found exactly what he’d been looking for. “That’s when I knew like, ‘Oh, this is what’s appealing to me, definitely, I know for sure now.’ Just shooting life as it is: not forcing anything, not staging anything, and trying to find something interesting in the so-called mundane.”

At that point, he was more or less addicted to road tripping and embarked on a 4,200-mile jaunt, shooting dozens of rolls of film and Polaroids, all while keeping a certain approach in mind, which he says goes back to the New York Museum of Modern Art, when a 30-year-old Wessel brought a stack of prints to the museum’s director of photography John Szarkowski. It was work that, Lee says, was Wessel’s attempt at a, “Life Magazine kinda thing—poor kids playing on a porch in the South with muddy faces and all this stuff, like American stories, which was great stuff.”

But then Szarkowski got to a photo of an old truck sitting in the middle of a field. “And Szarkowski said, ‘You need to shoot more like this. Instead of trying emulate this other thing and tell a story and get yourself in the mix, just remove yourself and shoot what’s there. Let the subject be the author, instead of you trying to tell a story with your camera.’ That changed the course of Wessel’s shooting.”

More succinctly, Lee sums up his approach with more of Szarkowski’s wisdom:

“The photographer’s vision convinces us to the degree that the photographer hides his hand.”

But his love of photography (and clearly, its history) isn’t limited to his own work or even the work of those who influenced him. Originally an Instagram hold-out—“I thought Instagram was just a bunch of memes and silly selfies and photos of food and people’s cats,” he says—Lee started the account Film Photographic just over a year ago, which describes itself as “a co-curated community gallery and resource page by and for film photographers.”

The website should be ready by the fall, he says, and he’s got big plans for it, including publishing their own coffee table books, collecting the work of Film Photographic community photographers in multiple volumes.

“It’ll hopefully be the first of its kind, in that it’ll be multiple galleries, resource pages, message boards, cameras and film for sale—like you can sell on there—and how-to videos, and a list of cool photo books and local camera shops all around the world. Just a really involved film resource website.”

Those who use those resources will be lucky to have Lee involved, as he’s got suggestions about everything from road trip routes (“Fly to Chicago, rent a car, and take old Route 66 all the way to California”) to the “weird line” between kitsch and sincerity while documenting it: “If there’s a genuine appreciation for that aesthetic or that architecture or the landscape or those contrasts, that environment, it’s gonna read as genuine.”

Maybe the best thing for photographers to take away from Lee, though, is that boundless, unexplainable enthusiasm he approaches his work with—his genuine love for the next trip, and the next shot.

“If I’m driving down some back road, and I see an old school bus in the middle of a field, and the only other thing there is an old rusted out basketball hoop, I don’t know why I wanna photograph that, but I do,” Lee explains. “I wanna put the basketball hoop on the left side of the frame, and I wanna put the back end of the school bus on the right side of the frame. I wanna contrast those two things and frame up my composition and take the photo, and I get excited about it! You’ll have people going, ‘Well that’s just a photo of an old school bus and a basketball hoop in the middle of a field.’ But for some reason for me, if I get the shot I like, I get really excited about it. I don’t know why.”

You can order Jason Lee’s new book from Refueled Magazine and follow Lee on Instagram for updates at @jasonlee

(All photos by Jason Lee/Portraits by Gay Ribisi)