Last December, American photographer Carol M. Highsmith received a letter from the Getty Images-affiliated photo licensing company Alamy, letting her know that she didn’t have a valid license to a photo used on her nonprofit’s website This America Foundation. They gave her a solution: pay them $120 for the licensing fee.

Highsmith knew the photo well —because she had taken it.

The shot of the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City was one of more than 18,000 photographs of American people and landscapes that she has donated to the Library of Congress for public use since 1988 (Highsmith has pledged to eventually donate 100,000 images).

Highsmith’s lawsuit, filed on July 25, 2016 in New York, alleges that Getty Images and Alamy “grossly misused” her photos, unlawfully charged licensing fees and fraudulently represented themselves as the exclusive copyright owner. She is suing the agencies for $1 billion.

No one likes it when a top photo agency strips the credit of the original photographer. But does Highsmith’s lawsuit have the potential to change the way business is done and how public images are licensed? Experts say this case, though interesting, likely won’t have a trickle down effect to photographers, especially since Highsmith voluntarily gave a high volume of images to the public.

What is the lawsuit about?

In a 1988 letter to the Library of Congress, Highsmith dedicated her collection “to the public all rights, including copyrights throughout the world.” Her images have been featured on postage stamps, in feature films and in the television show House of Cards.

“At no time did Ms. Highsmith intend to abandon her rights in her photographs, including any rights of attribution or rights to control the terms of use for her photographs, nor was it ever her intent to enable third parties to purport to sell licenses for her photographs, or send threatening letters to people who used her photos,” the complaint reads. “At all times relevant to this lawsuit, Ms. Highsmith’s intent has been that the public should be able to reproduce and display her work for free, with proper accreditation given to her and proper reference made to the Library collection.”

The lawsuit alleges not only that Getty and Alamy did not properly credit Highsmith as the copyright holder, but that they claimed to hold the copyright. Both sites have since removed her images.

The suit says that U.S. copyright law entitles Highsmith to collect damages between $2,500 and $25,000 per violation. The lawsuit alleges Getty violated copyright at least 18,755 times, which means Highsmith could collect up to $468,875,000 if the violations are proven.

Alamy had approximately 500 of Highsmith’s photos on the website, according to the complaint, and could be fined up to $12.5 million if Highsmith proves her case.

Highsmith and her lawyers declined to be interviewed for this story, citing pending litigation.

Getty released a statement that said they believed the complaint is “based on a number of misconceptions.”

“The content in question has been part of the public domain for many years. It is standard practice for image libraries to distribute and provide access to public domain content, and it is important to note that distributing and providing access to public domain content is different to asserting copyright ownership of it,” the statement reads.

Are these actually public domain images?

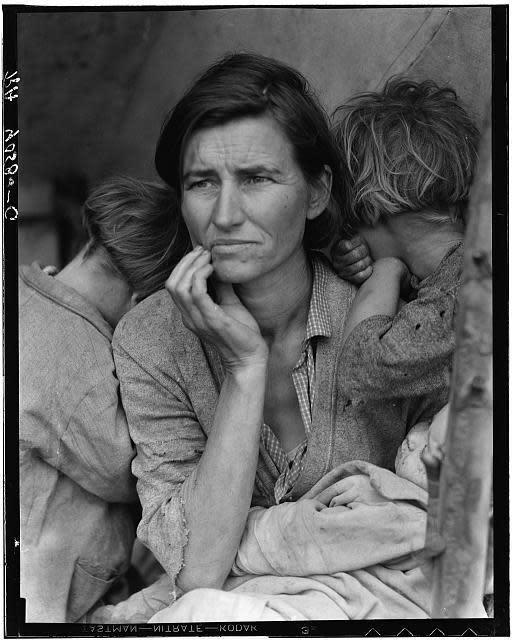

Photography in the public domain, already available from the Library of Congress, are available for purchase on sites such as Getty Images. The iconic Dorthea Lange photo of a woman and her children that epitomizes the Dust Bowl era is a public domain image available through the Library of Congress, and also available for purchase on Getty and Alamy.

“As a filmmaker I’ve encountered this on several occasions, I want to use an image that is fair use, I don’t have any obligation to pay a licensing fee, even to the legitimate copyright owner, but I don’t have access to a high quality version,” said Brian L. Frye, an associate professor at the University of Kentucky College of Law who teaches classes in copyright. Frye said you end up paying a fee to license the higher quality image.

“Getty is fast, their business is getting to people in journalism who need [images] yesterday. There’s value added there,” Frye said. “The problem here is they took Library of Congress material and claimed they owned something they didn’t.”

Frye said the major question that needs to be answered in this case is if Highsmith’s images are actually public domain. “If copyright is all pervasive and can’t be ended,” Frye speculated, it would be “surprising” if the court decided an individual can’t donate images to the public.

“The complaint is a scattered attempt by attorneys to say that these photographs weren’t really donated,” Frye said. They are trying to treat the photos as if they have a Creative Commons license (which didn’t exist in 1988).

“If they are donated photos, neither she nor anyone else would be the owner, she wouldn’t have the rights and neither would anyone else.”

What does this lawsuit mean for the future of public domain images?

Frye said this is a common law fraud case or wire fraud case, not a copyright issue. He doesn’t think the lawsuit will make it too far through the courts.

“If Highsmith wins, then every museum in the country that circulates images of public domain art and claims a copyright is now violating a provision of the law. And anyone asked to pay a fee [for a digital image or transparency] would have a right to bring an action against a museum. It would be destructive and not make any sense at all,” Frye said.

Robert Jacobs, a litigation partner in Manatt, Phelps & Phillips LLP, said the court will determine if Highsmith retains the rights to her photos, or relinquished them when she gave the photos to the Library of Congress.

The Highsmith case has been compared to a 2013 ruling that found Getty and Agent France-Presse violated U.S. copyright law when they sold images posted by a photojournalist to Twitter after the Haiti earthquake. But, Jacobs said, the Highsmith case has more similarities to the “Happy Birthday” copyright case. In 2015, a federal judge ruled that companies had been improperly collecting royalties on the popular song for the past 80 years. (Jacobs did not work on that case, but has represented Warmer/Chappell, the company that previous held the song’s copyright).

“It sounds like someone made an aggressive decision to upload and claim ownership of works that should have been,” Jacobs said of the Getty case. “It could have been a mistake or more nefarious, I don’t know, but the issue is whether Getty acted improperly.”

All images by Carol M. Highsmith (except for cited Dorthea Lange) via Library of Congress